Chapter 1 Resources

“The New Negro” Textbook Chapter (Part IV)

For an introduction to the Harlem Renaissance, see part IV in this chapter from American Yawp, an online open American history textbook.

This exhibit by the New York Public Library Schomburg Center includes photos and descriptions of Black life in Harlem from 1900-1940, focusing on important people, events, and movements.

The Modern School [Link coming soon]

This website from the Harlem Education History Project contains a variety of materials from the sixty-year history of the Modern School. Although most of the oral histories and primary sources cover later periods than chapter 1, they give insight into Mildred Johnson’s educational philosophy and the experiences of Modern School students from the 1950s on.

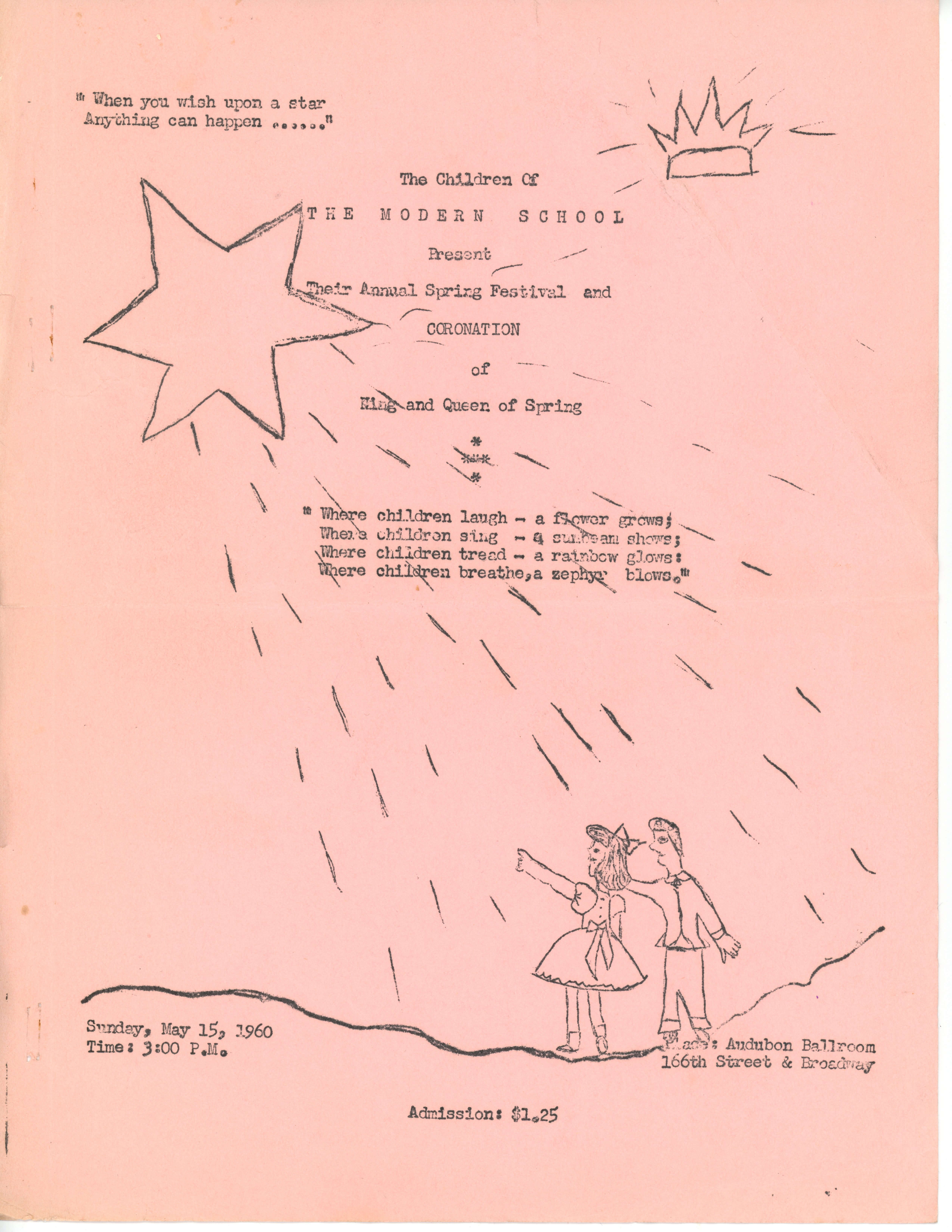

Program from the Modern School’s Annual Spring Festival, 1960. Credit: Cherilyn Wright.

In a blog post for the Association of Black Women Historians, Deirdre Flowers writes about Mildred Johnson and researching the Modern School as a former student.

Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing (1900-present)

Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing is also known as the “Black National Anthem.” It was written by James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosamond Johnson, the father and uncle of Modern School founder Mildred Johnson. For more, see this new digital humanities project that collects public recordings of the song, and read Imani Perry’s book, May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem.

Photographs of James Weldon Johnson, J. Rosamond Johnson, Mildred Johnson, Countee Cullen, and Langston Hughes (1932-1941)

These digitized portraits of some of the people discussed in chapter 1 are part of the collection of Carl Van Vechten, a writer and photographer who took portraits of many notable figures of the Harlem Renaissance.

The Amsterdam News (1909-present)

The Amsterdam News is a Black newspaper based in Harlem, which was founded in 1909. Those with access to ProQuest Historical Black Newspapers from a local public library or university can search “The Modern School” or other topics from the chapter to learn how they were covered in the Black press.

Photograph of Sugar Hill (1938)

In this photograph, the Sugar Hill neighborhood is visible on the hill above the park. Sugar Hill was home to many wealthier Black residents of Harlem in the 1920s. Its boundaries are West 155th Street to the north, West 145th Street to the south, Edgecombe Avenue to the east, and Amsterdam Avenue to the west.

This issue of The Crisis includes poems by two authors discussed in chapter 1, Countee Cullen (p. 22) and Jessie Fauset (p.26). The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, was started in 1910 under founding editor W.E.B. Du Bois. During the Harlem Renaissance it was notable for its literary publications, with Jessie Fauset serving as the literary editor. Many other editions of the magazine (1910-present) are available online.

Gertrude Ayer was a leading educator in Harlem, who implemented progressive methods of education as principal of P.S. 24. Her 1925 essay, “The Double Task,” was published in Survey Graphic and was included in The New Negro, an anthology of Black literature edited by Alain Locke. In it, Ayers discussed the double oppression Black women faced on the job and at home.

In chapter 1 of Educating Harlem, Perlstein highlights “Kabnis,” which tells the story of a Black teacher’s experience teaching in the South. The text was the final chapter of the novel Cane, written by Jean Toomer and published in 1923.

Written by Nella Larsen, the novel Quicksand centers on a teacher who worked at a southern boarding school, based on the Tuskegee institute. Quicksand is analyzed in chapter 1 of Educating Harlem to discuss the intersections between race, literature, and education in the Harlem Renaissance.

The Brownies’ Book was a children’s supplement to The Crisis published by the NAACP. In chapter 1 of Educating Harlem, Perlstein writes, “The Brownies’ Book balanced progressive pedagogy’s vision of self-directed activity with the need to transmit an alternative to the identities that a racist world had assigned Black children.”

Discussion Questions

-

Browse these primary sources from The Modern School, kept by students who attended in the 1950s and 1960s. How do these sources align with or diverge from the impression of the Modern School you got from the chapter?

-

What new information did you learn about the Harlem Renaissance? How does this chapter’s discussion of the Harlem Renaissance compare to others that you have read?

-

Educators often contrast “constructivist” modes of learning, where students build knowledge through experience and inquiry, with “direct instruction,” where teachers present knowledge for students to absorb. How did Renaissance educators depict these modes of learning? How did they relate to one another? How did the experiences of Black Americans at the time shape these ideas about education?