Chapter 9 Resources

“Black Power!: The Movement, The Legacy” Exhibit and Resource Guide

This exhibit from the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center provides an introduction to the Black Power movement, including its organizations, leaders, and activities. This accompanying resource guide suggests books, videos, recordings, and other electronic resources to explore for more information.

“The Black Panther Party: Challenging Police and Promoting Social Change”

The National Museum of African American History and Culture’s post provides an introduction to the Black Panther Party. It includes videos and primary sources from the Black Panther Party’s history, and discusses its range of commitments including militant protest, radical social change, and social reforms to address hunger and improve education and housing.

“Reimaginers: The Young Lords” Interview with Johanna Fernández

In this interview with Matt Kautz and Christina Martin for the Center on History and Education, Johanna Fernández discusses her book, The Young Lords: a Radical History (2019). Fernández gives an overview of the Young Lords’ goals and activism, making connections to schooling today. She discusses the experiences of Puerto Rican students in New York City schools in the 1960s, the group’s radical vision for change, and the peer-to-peer teaching they modeled.

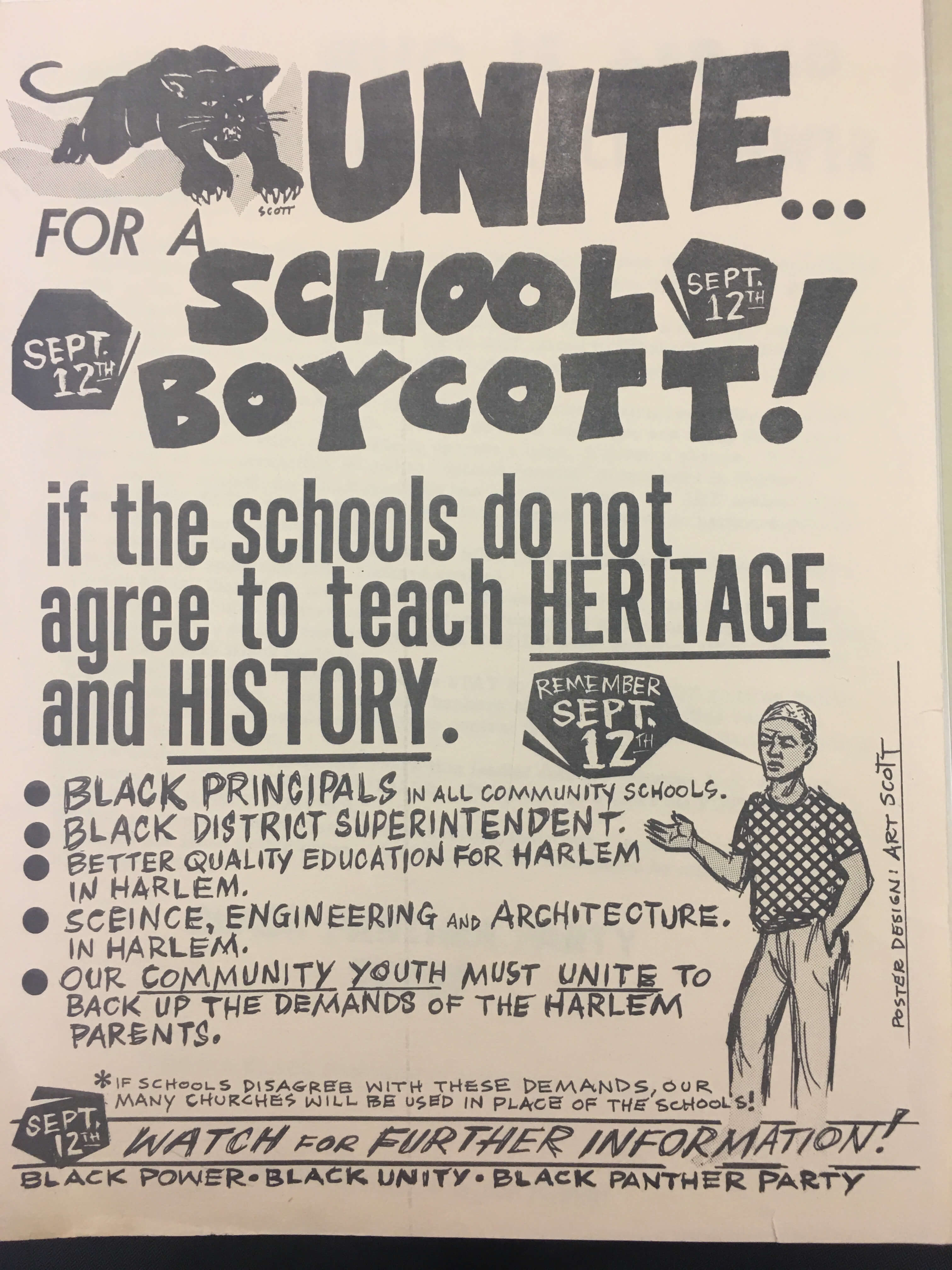

“Unite for a School Boycott!” (1966)

This 1966 flyer from the New York Black Panther Party called for a school boycott in Harlem, with demands for Black principals in all Central Harlem schools, the teaching of African and African American history, and other improvements for quality education in Harlem. This was one of many ways that the Black Panther Party engaged in education and social reform, also including leading educational activities, providing free breakfasts for school children, and supporting other school protests. For more on the New York branch of the Black Panther Party, see this Amsterdam News article from the 50th anniversary of the founding of the party’s second iteration.

“Unite for a School Boycott” Flyer, 1966. Credit: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Photograph of Malcolm X (1952-1959)

Malcolm X was a Black Nationalist leader in Harlem who led the Nation of Islam and founded the Organization of Afro-American Unity in the 1960s. During his life, and particularly after his assassination in 1965, Malcolm X influenced the grassroots educational spaces in Harlem that chapter 9 author Russell Rickford calls “a tremendous wellspring of militant energy.” This portrait is part of the digital collection of the New York Public Library.

Photograph of 116th Street Mosque

The Nation of Islam’s Harlem mosque was the site of a number of educational programs in the 1960s and 1970s. After Malcolm X’s assassination, the mosque was destroyed by a firebomb, and was rebuilt in its current form to include a school called “The University of Islam” as well as Nation of Islam businesses. This photograph is part of the Schomburg Center’s “Black New Yorkers” exhibit.

Organization of Afro-American Unity Inc. Aims and Objectives (1964)

Malcolm X founded the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) in 1964, after he split from the Nation of Islam. Rooted in principles of Pan-Africanism and human rights, the OAAU started a weekly Liberation School at the Hotel Theresa on 125th Street in Harlem, which held free classes for children and adults. The organization’s objectives are detailed in this pamphlet from 1964.

Audley “Queen Mother” Moore Oral History and Black Perspectives Blog Series (2019)

Audley “Queen Mother” Moore was a Black Nationalist leader, with a history of activism for tenants rights, socialist, and reparations movements. In the 1960s, Moore worked to establish an independent school on her estate “Mount Addis Ababa” in upstate New York. She envisioned an education “totally embracing the cultural, educational and industrial needs” of its Black students. The school never opened, but schoolchildren did visit for special activities.

Photograph of National Memorial Bookstore (1960) and The Black Bookstore Research Guide

National Memorial Bookstore was opened by Lewis Michaux in the 1930s. It sold books by and about Black people and culture and was a center for political expression in Harlem. The Schomburg Center’s Black Bookstore Research Guide provides suggestions of further reading on Black bookstores like National Memorial.

“On Black Aesthetics: The Black Arts Movement” (2016)

The Black Arts Theater/School was founded by LeRoi Jones, later named Amiri Baraka, in 1965. The organization sponsored plays and exhibits for the Black community of Harlem and offered classes with leading Black artists. It contributed to the formation of the Black Arts Movement in the 1960s, which grew alongside the Black Power Movement. This post from the New York Public Library introduces the Black Arts Movement, and links at the bottom to a digital exhibit called “Ready for the Revolution: Education, Arts, and Aesthetics of the Black Power Movement.”

Photographs of National Memorial Bookstore, the Yoruba Temple, and the Black Panthers’ Free Breakfast for School Children

The Black New Yorkers Exhibit exhibit from the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center surveys 400 years of Black history in New York City. The exhibit includes essays divided by time period and a large gallery of photographs that depict important events, people, and aspects of daily life, including these sites discussed in chapter 9.

Discussion Questions

-

What are the most common images or stories that you associate with the phrase “Black Power”? How does author Russell Rickford’s description of the Black Power educational landscape align with or differ from those images or stories?

-

Rickford helps readers see how Black activists imagined educational spaces that aligned with and would help them achieve their broader social and political goals. In this video, educators respond to the question, “What are schools like in Wakanda?,” playing off of the fictional 2018 film Black Panther to encourage expansive thinking about what is possible in education. What do the video, and Rickford’s chapter, suggest about the power of imagining and working towards new visions of education in Harlem or beyond?