Chapter 10. “Harlem Sophistication”: Community-based Paraprofessional Educators in Central Harlem and East Harlem

by Nick Juravich

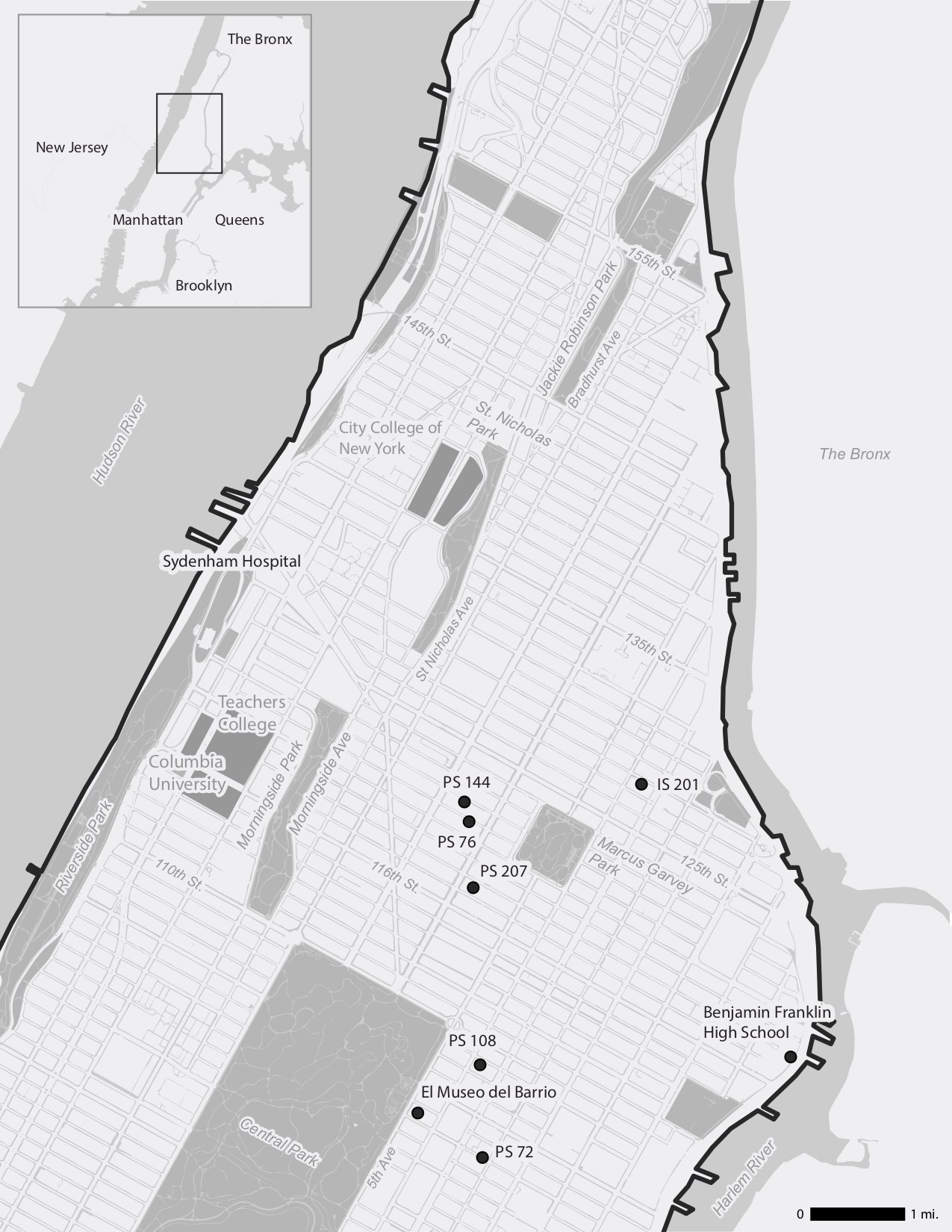

Map design by Rachael Dottle and customized for chapter by Rachel Klepper. Map research by Rachel Klepper. Map layers from: Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, Department of Urban Planning, City of New York; Atlas of the city of New York, borough of Manhattan. From actual surveys and official plans / by George W. and Walter S. Bromley New York Public Library Map Warper; Manhattan Land book of the City of New York. Desk and Library ed. [1956]; New York Public Library Map Warper; and State of New Jersey GIS. Point locations from: School Directories, New York City Board of Education, New York Amsterdam News via ProQuest Historical Newspapers, and multiple archival sources cited in relevant chapters. See maps of the locations discussed in the full volume here.

Winifred Tates applied to work at Public School (PS) 72 in East Harlem “to be an inspiration to her children,” as she told an evaluator in 1976. This evaluator described Tates as “very community oriented,” an educator who did “great things with children.” She “was involved with everything” at her school, including classwork, home visits, and field trips, and she had guided a reading group of “the lowest achievers in the class” up to grade level. When observers from the Board of Education visited PS 72, they “constantly mis[took] her for the classroom teacher.”1

In fact, Tates was a paraprofessional educator, working in a new kind of community-based position that was envisioned by parents, educators, and activists in Harlem in the 1960s. As part of their struggles for educational equity and self-determination, these Harlemites pushed the Board of Education to hire local residents—primarily the mothers of schoolchildren—to work in public schools. Local hiring, they argued, would create jobs for poor and working-class Black and Latina women, improve the quality of education for their children, and connect local schools to their communities. To transform Harlem’s schools, these activists reimagined the work of education: who should do it, how they should do it, and how communities should know about it.

Plans for community-based hiring germinated in Harlem’s antipoverty organizations, where staff and participants challenged psychological and cultural explanations of poverty by empowering Harlem’s residents in the early 1960s.2 Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU) played a central role, cultivating demonstration programs and petitioning the Board of Education to deploy federal funds for local hiring. Their efforts yielded fruit when the board hired its first paraprofessional educators in the spring of 1967.

By then, Harlem was in the midst of a “renaissance of educational thought and practice” inspired by the Black Power movement.3 Community-based educators blossomed in this hothouse. The first generation of “paras” went beyond official expectations for their positions, implementing new pedagogies, curricula, and community outreach. Their labor proved so valuable to students, teachers, and parents that the board hired over ten thousand paras by 1970.

To secure their jobs during the political upheavals that rocked New York’s schools in these years, paraprofessional educators organized, waging an innovative campaign in their neighborhoods and within their union, the United Federation of Teachers (UFT). The contract they won provided living wages, job security, and opportunities for advancement to thousands of working-class Black and Latina women. As a result, the ideas, practices, and organizing strategies of Harlem’s community-based educators became models for a national “paraprofessional movement” that brought half a million new workers into U.S. public schools by the time Winifred Tates was interviewed in 1976.4

Despite the movement’s success, New York City’s 1975 fiscal crisis generated severe cuts in programs and positions for paraprofessional educators.5 The politicians who emerged from this crisis in power sought to perpetuate austerity policies and to redefine the work of education as the province of elites. Community-based educators fought back and kept their jobs; 25,000 paraprofessional educators work in New York City today, out of 1.2 million nationally. However, the broad, emancipatory vision of community-based educational work that Harlem’s first generation of paras practiced became a casualty of the crisis as the resources, institutions, and activism that had sustained it withered in this new, hostile educational climate.

This essay explores the evolving practice and meaning of educational work for Harlem’s community-based paraprofessional educators over two decades. In their struggle for good jobs and permanent careers in public schools for local mothers, Harlem’s activists channeled demands for jobs and freedom that reverberated through the Black freedom struggle, from the March on Washington to New York City.6 By asserting that working-class Black and Latina women could work as educators and improve schooling, these Harlemites challenged the views of elite policy makers who believed poor women and their neighborhoods were in thrall to a “culture of poverty.”7 Through their labor, the first generation of community-based paraprofessional educators remade the classroom experience and relationships between schools and communities. Through their organizing, they made their jobs permanent, institutionalizing a new kind of educational work that persists to this day as a legacy of the Black freedom struggle.

The meanings of this work were always contested, even within the coalition of Harlemites who supported and worked in community-based jobs. The integrationist socialist Bayard Rustin and the radical nationalist Preston Wilcox both campaigned for local hiring. They debated the ways in which these workers should be prepared, how they should be organized, and what they should do in classrooms. The decision to unionize, in particular, cast these contests in stark relief: a contract offered stability, legitimacy, and advancement in schools, but institutionalization necessitated trade-offs and compromises that dismayed radical organizers. Across the city, the women who did this work struggled constantly to assert the value and legitimacy of their labor in the face of elite critiques and, later, tightening budgets. At one level, this is the story of a Harlem struggle that produced lasting changes in the American educational workforce. At the same time, charting the rise and fall of community-based educational work in Harlem reveals a rich, forgotten praxis that was undermined not by ineffectiveness, but by austerity politics.

Envisioning New Kinds of Educators in Harlem

Three factors generated demands for local hiring in Harlem schools in the early 1960s. First, New York City’s teaching corps was very segregated by northern standards; Harlem’s teachers knew little of their students’ lives and often feared their neighborhoods.8 Second, as students weathered segregated, indifferent learning environments, their parents struggled in a segregated, deindustrializing economy. As New York lost thousands of manufacturing jobs and added thousands of public-sector ones in the postwar era, access to city work took on heightened importance. Finally, the rise of federally funded antipoverty programs in New York, including HARYOU (founded in 1962), created spaces for experimentation in local employment.9

Parents and educators affiliated with HARYOU used demonstration programs and direct advocacy to push the Board of Education to hire locally. Richard Parrish was a Harlem teacher and union organizer who coordinated volunteers for Virginia’s freedom schools in the summer of 1963. That fall, Parrish recruited two hundred teachers to work with students alongside four hundred mothers hired by HARYOU.10 The afterschool program helped students “associate with adequate role models on a more personal level” and promoted “parent and teacher cooperation.”11 Later that year, Thelma Johnson, the chair of HARYOU’s Committee on Education and the Schools, petitioned local administrators “to pay female recipients of Welfare” to walk children to and from school. The program, Johnson argued, “would serve the dual purpose of getting the children to school and providing the Welfare recipient with a sense of pride.”12 Johnson and Parrish knew that Harlem’s parents would make talented educators if given the opportunity, and they understood that working-class people needed to get paid for their work.

HARYOU summarized its educational philosophy in its 1964 report, “Youth in the Ghetto.” Among “ten anticipated needs” for Harlem’s youth, HARYOU listed “parent aides” who would “demand for them [Harlem youth] what middle-class parents demand.” The social worker Laura Pires wrote in the report that hiring “indigenous nonprofessionals” in public roles would “improve the giving of service” and create “meaningful employment for Harlem’s residents.”13 Pires’s colleague, the sociologist Frank Riessman, agreed. He quoted her in the frontispiece of his 1965 book with Arthur Pearl, New Careers for the Poor, adding, “This statement, taken from the HARYOU proposal, forms the basic thesis of this book.”14 Pearl and Riessman’s book pushed the idea of local hiring into the policy mainstream and spawned a “New Careers Amendment” to the Economic Opportunity Act, introduced by Congressman James H. Scheuer of the Bronx in 1966. The core concepts, as Riessman acknowledged, were forged in Harlem.

The call for community control of Intermediate School (IS) 201 in 1966, discussed at greater length in chapters 8 and 9 of this volume, reshaped educational organizing in Harlem and amplified demands for local hiring. The scholar-activist Preston Wilcox called for a “fundamental restructuring of the relations between school and community based on a radical redistribution of power,” which included “training local residents as foster teachers.”15 The Harlem Parents Committee called for local hiring in their newsletter, as did the mayor’s commission in its 1967 report on decentralization.16

Starting in 1966, Wilcox chaired the board of the Women’s Talent Corps (WTC), a job-training institute for women funded by the Office of Economic Opportunity. The WTC began training Harlem-based women for paraprofessionals jobs after Wilcox organized meetings with local community associations to forge partnerships. Seeking to place aides not just in community-run programs but the public schools themselves, the WTC and its trainees conducted letter-writing campaigns and a sit-in at the Board of Education. Their seventy-five trainees became the first paraprofessional educators hired by the board in 1967.17

Community-Based Educators at Work, 1967–1970

The Board of Education expanded hiring to 1,500 people in the fall of 1967 and employed more than 10,000 paraprofessionals by 1970. A study conducted in that year offers a statistical portrait of these educators. Half of New York’s paras were African American and close to 40 percent had Spanish surnames (for context, only 42 percent of students were white but 91 percent of teachers were). Some 93 percent of paras were women, 80 percent of whom were mothers living within ten blocks of the schools where they worked. Their children attended these schools, and 85 percent regularly saw their students outside the classroom. Furthermore, 60 percent of paras reported formal involvement in a community institution, and nearly all cited increased engagement with neighbors through their new jobs. They worked an average of twenty-two to twenty-five hours a week and took home roughly $50, just above minimum wage. Federal regulations required that all job applicants be on welfare or eligible for it.18

As this study indicates, paras entered classrooms with intimate knowledge of the needs of local families and long-standing connections to community organizations. The Board of Education’s hiring structure cemented these connections. Half of paras were nominated for their positions by city-recognized “Community Action Agencies,” including HARYOU-ACT.19 Principals hired the other half from among parent leaders and existing school staff. Organizations including HARYOU-ACT and the Women’s Talent Corps provided training.

The talents and connections paras brought to their work completely undermined the “culture of poverty” thesis then in vogue with many poverty warriors. Anne Cronin, the training director at the WTC, rejected this framework explicitly, writing that the WTC’s training program “reflects a basic philosophy about the ‘teachability’ of uneducated people. It assumes that the ‘culture of poverty’ does not affect the attitudes of most of the low-income groups in New York City.”20 As Cronin added in 1968, her students “were people who are alert and active in community affairs . . . PTA officers, den mothers, community council members, church volunteer workers . . . with a rich life-knowledge and wisdom about the ways of their world.”21 Laura Pires, who moved from HARYOU to the WTC to support trainees in the field, developed her own shorthand for this combination of local knowledge and organizing savvy. She called it “Harlem sophistication.”22

Paraprofessionals in Central Harlem and East Harlem represented the diversity of these neighborhoods by design, and they tailored their work to the needs of their particular school communities. Across these diverse settings, they deployed three general strategies to succeed in their new roles. First, they practiced “activist mothering,” the promotion of youth and community survival through the use of “indigenous knowledges.”23 Second, they built cross-class, interracial solidarity among working women that connected local mothers, paras, teachers, and union organizers. These alliances helped paras secure their jobs.24 Third, paraprofessional educators consistently sought education and training to turn their jobs into teaching careers, espousing a philosophy of collective advancement that sought to rise with Harlem rather than from it.25

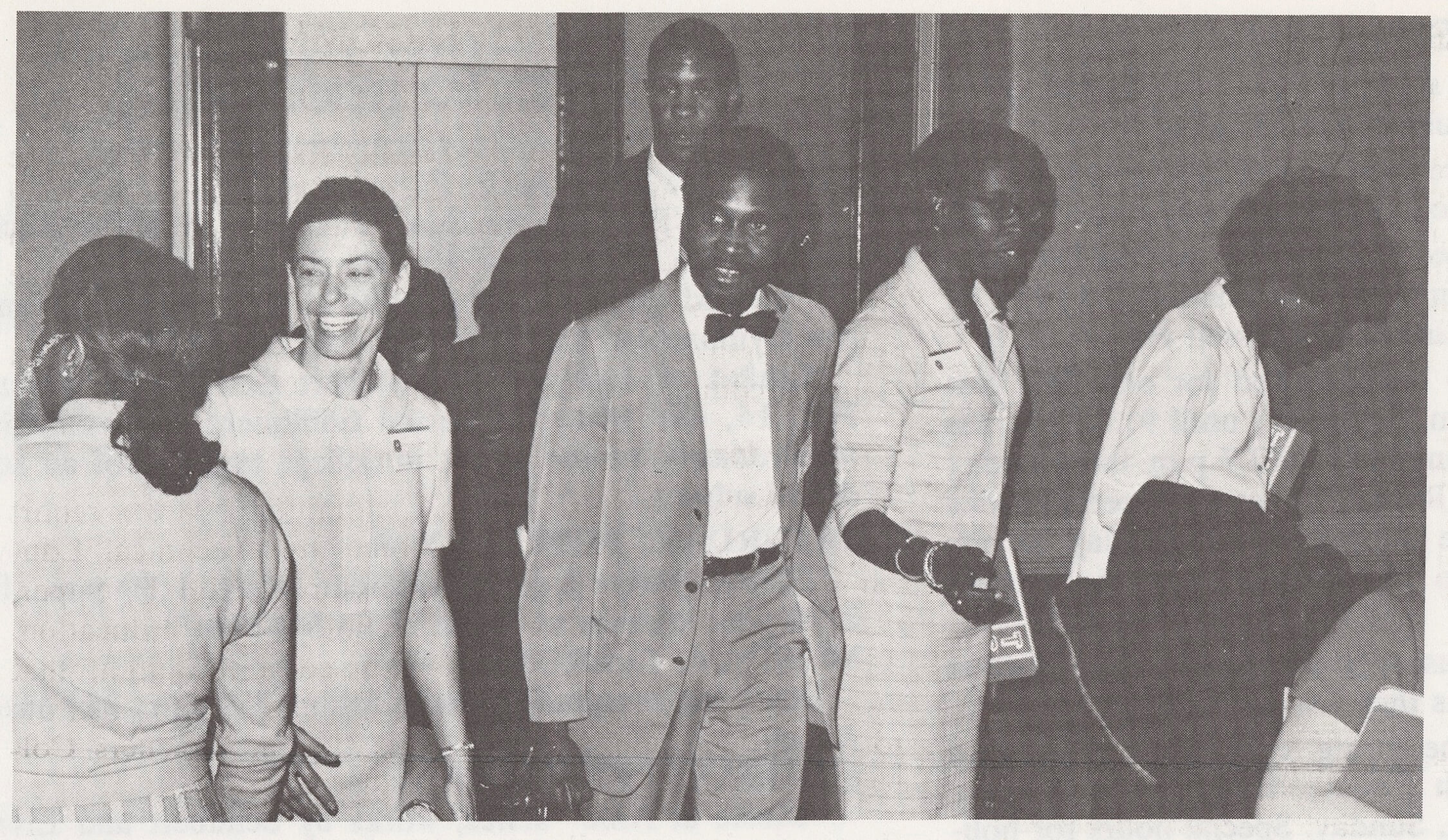

Figure 10.1 Professor Hope Leichter (second from left) talks with parent participants in the Parent-Teacher Teams program at Teachers College in 1969. Credit: TC Week, February 1969.

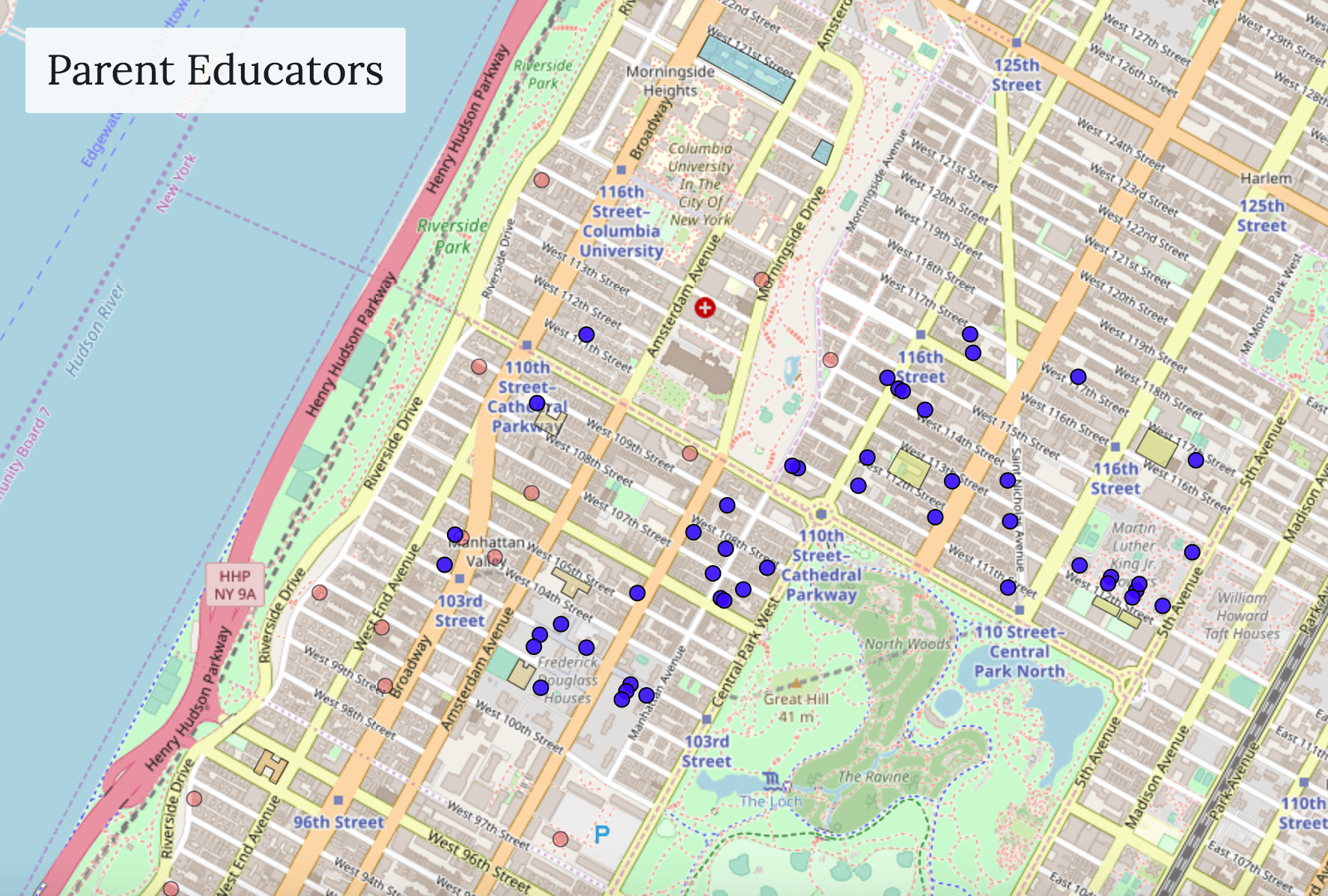

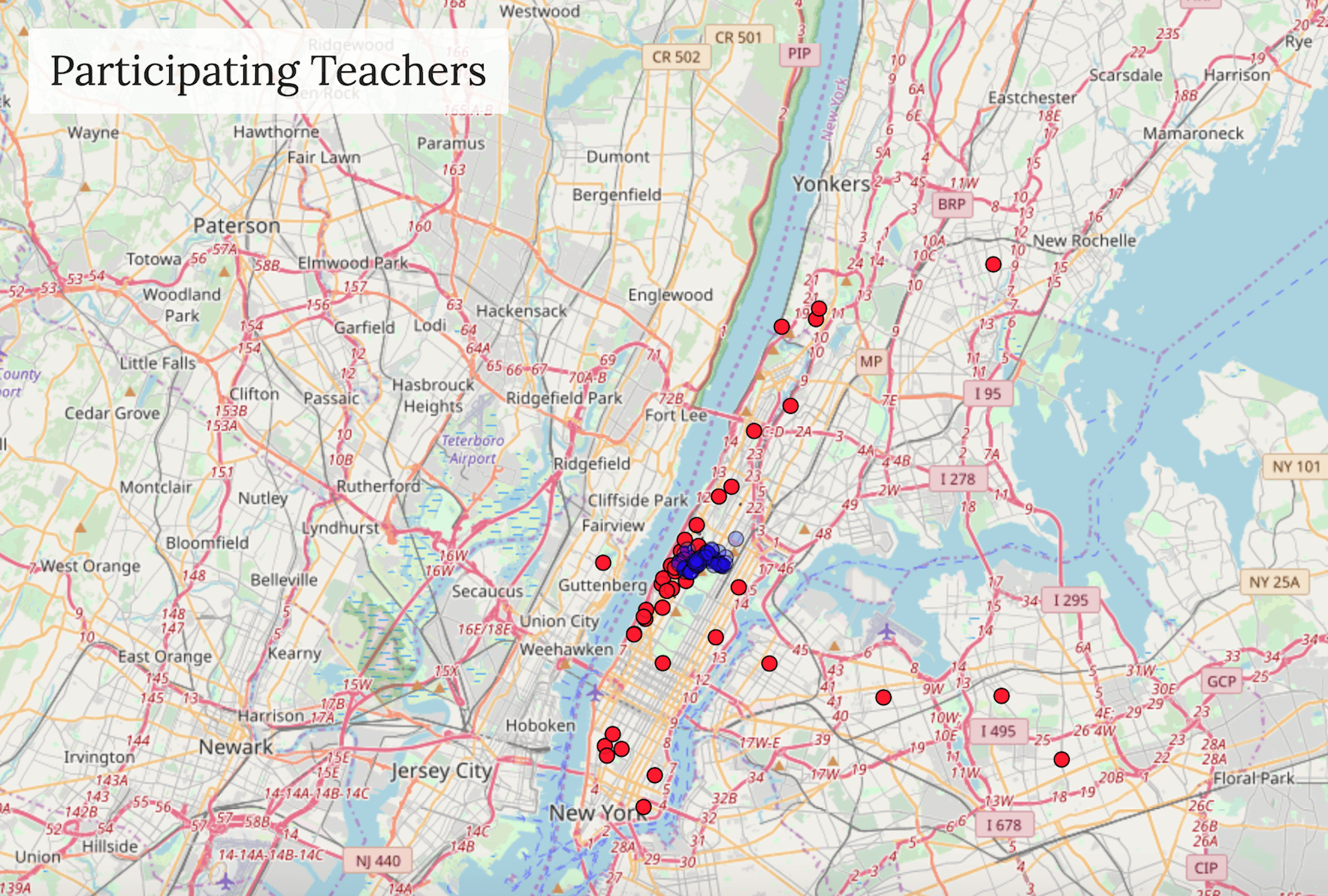

A detailed look at a single program reveals the many facets of community-based educational work. Parent-Teacher Teams (PTT) was developed jointly by HARYOU-ACT, Local School District 5, and Teachers College. The program employed 130 parents in 27 schools in Harlem and the Upper West Side, serving 3,900 students between 1967 and 1970.26 At one cluster of four schools in southern Harlem, 26 of 27 paras hailed from the same ten-block radius (one lived just outside), but only one teacher lived in the neighborhood, on Morningside Avenue. These mothers, who were in regular contact with the families they served, connected the schools to the community in ways that teachers, who were often commuting from outside Harlem, could not.

Figure 10.2 Blue dots mark the homes paraprofessional educators hired to work in two Parent-Teacher Teams clusters in 1967. The schools where they worked are outlined in yellow. Cluster B encompassed four schools in Southern Harlem, above Central Park and east of Morningside Park. Cluster C encompassed three schools in Manhattan Valley and Morningside Heights, west of both parks. Source: Addresses of Participating Teachers and Parents, Morningside Area Alliance Collection, Series 3, Box 55, Folder 16, Parent Teacher Teams, Columbia University Archives.

Figure 10.3 Red dots mark the homes of teachers paired in classrooms with the paraprofessional educators whose addresses are mapped in Figure 2. Only one teacher lived in Harlem. Several lived on the Upper West Side, while others lived in faraway suburban neighborhoods. Source: Addresses of Participating Teachers and Parents, Morningside Area Alliance Collection, Series 3, Box 55, Folder 16, Parent Teacher Teams, Columbia University Archives.

The proposal for Parent-Teacher Teams outlined a bounded, gendered definition of paraprofessional labor. It included suggestions for tasks such as “contribute to enrichment activities by utilizing her special talents,” “alert the teacher to the special needs of individual children,” “give special encouragement and aid to the non-English speaking child,” and “be a source of affection and security to the children.”27 The women who did this work fulfilled these roles, but they also expanded on them, leading efforts to affirm students’ language, culture, and experiences. At PS 207, Azalee Evans developed the first African American history curriculum.28 In all PTT schools, paras served as translators for students and created bilingual materials for them and their parents.29 As an assessment of the program’s first year asserted, “The addition of a parent in the classroom benefits the children as much as the teacher and parent involved” because such a worker could “relate to children whose environment she shares.”30

During the most contentious years in the history of public schooling in New York City, Parent-Teacher Teams garnered rave reviews. After a trial summer program in 1967, one teacher declared, “I can’t wait to have a parent in my room.” A parent replied, “I used to be so afraid of the school. Now I know it is a friendly place.”31 In February 1969, a PTT principal told reporters that the program “worked beautifully,” a view echoed citywide.32 In May 1968, the UFT released a survey of over 200 teachers, nearly all of whom loved these new workers. One noted the value of having a bilingual adult in the classroom, and another explained that she had been “so much more successful because of her [para’s] assistance, especially reaching out to parents.”33 The survey also reached 230 paras, of whom only 4 reported negative experiences. Their responses revealed strong commitments to local children and the goal of “establish[ing] a closer relation between parents and schools.” Paras also asserted their need for prompt pay and living wages, and hoped the Board of Education would make good on the promise of teacher training.34

The UFT’s report revealed emerging solidarity between classroom workers. Paras and teachers brought mutual suspicions into their classrooms, but the time they spent together generated goodwill among those who shared the challenges of working women. As one PTT teacher explained, working with paras had taught her that “parents want the same thing that I want—each is looking out for the welfare of the child.”35 A Bronx activist later recalled that this first generation of paras had “made themselves essential” to students, parents, and teachers. In doing so, they laid the groundwork for a citywide campaign to secure their jobs.36

Securing Para Jobs with Unionization and Community Organizing

When the UFT’s report on paraprofessional educators appeared on May 20, 1968, no one was paying attention. Nine days earlier, the Ocean Hill-Brownsville administrator Rhody McCoy had transferred eighteen white teachers out of his district, igniting a conflict between the largely white, middle-class UFT and Black and Puerto Rican community organizers that had been gathering fuel for a decade. By the fall, the union was out on strike and parent organizers in Harlem were sleeping in their schools to keep them open. Paraprofessional programs came of age as New York City’s school system came apart.37

During the 1968 strikes, many paras crossed picket lines to teach, particularly in the three “demonstration districts,” which included Harlem’s IS 201 complex. Preston Wilcox asked the trainees of the Women’s Talent Corps to do so, and many volunteered to work in these schools when their own were closed. Other paras stayed out in solidarity with the teachers they worked alongside.38 These same paras frequently staffed “freedom schools” hosted by churches and community centers. On either side of the picket line, paras did the work of education for neighborhood children (and their parents, who desperately needed child care). The experience made a powerful impression on paras. As several WTC trainees told Laura Pires afterward, their work during the strikes had simultaneously convinced them of the importance of their positions and raised fears that “experimental” paraprofessional programs, like those housed in the demonstration districts, could be shuttered at any moment.39

Although paraprofessional educators had expressed interest in unionizing before the strikes, the UFT’s scorched-earth attack on community control seemed to foreclose the possibility of any further partnership. In addition, the strikes badly divided the UFT’s membership. Richard Parrish published a searing critique of his union subtitled “Blow to Education, Boon to Racism,” in which he denounced the strikes and urged teachers to depose the leadership in favor of a “genuine partnership between the UFT and the black and poor communities.” Parrish added, from experience, “unless Black and Puerto Rican people have a chance to get on the staff, to have job training and to develop as their white counterparts, they will never be able to hold their heads up and work” in either schools or the union.40 Other opposition groups that emerged during 1968, including Teachers for Community Control, likewise supported the empowerment of paraprofessionals.41

The UFT’s president Albert Shanker publicly excoriated anyone who crossed picket lines in 1968. However, facing pressure from his union’s left flank and public perceptions of his union as a racist organization, , and with clear evidence that paras sought the benefits of unionization, Shanker embraced them. At the recommendation of Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, two of the only Black leaders to support the UFT during the strikes, Shanker put Velma Murphy Hill in charge of renewing the campaign. Hill, a Chicago-born protégé of Rustin, had cut her teeth in New York on the Congress of Racial Equality’s campaign to desegregate construction work at the State University of New York’s Downstate Medical Center in 1963.42 Like Rustin, she believed that integrated workplaces and public job creation were central to the future of the freedom struggle.43

An election was set for June 1969 between the UFT and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) DC 37, which was considered a far more progressive union. Hill and her team worked hard to define the UFT as an educator’s union with “the experience and strength to obtain professional pay and status” for paras.44 A report in the Baltimore Afro-American shared a different perspective, quoting the Harlem para Carolyn Frazier as saying, “I’m going to the highest bidder.” Responding to this, the WTC faculty member Robert Jackson explained, “The paraprofessionals ideologically prefer DC 37, but from a practical standpoint, they feel that the UFT has more muscle.”45 These comments highlighted a tension in the campaign: although it seemed clear that the UFT was better positioned to secure community-based educational work, this was the union that had just crushed the city’s boldest experiment in community control of schools. Given the vast disparities of power between working-class women and the largest local teacher’s union in the country, several historians have argued that paraprofessional unionization amounted to little more than co-optation by the UFT leadership. If this was the case, paras were remarkably clear-eyed about it.46

In June, just enough paraprofessional educators chose the “school union” to give the UFT a fifty-three-vote victory (out of roughly 3,800 cast). Years later, two Bronx leaders who had fought the UFT during the 1968 strikes voiced approval of the vote, citing the importance of “institutionalizing” para jobs. They also supported bringing Black and Latinx voices into the UFT to make it more responsive to communities.47 Paraprofessional educators had put their faith in the “union of professionals” (as the UFT described itself) to provide them with professional status without undermining their commitments to community-based educational work.

However, the Board of Education refused to bargain, daring paras to strike. Administrators believed the UFT’s white rank and file would never walk out in support of paras, and that if the union did strike, the Black and Puerto Rican communities who had fought for local hiring would turn on paras and support the board in breaking their union. In response, paras and their union waged a novel two-front campaign in neighborhoods and union halls.

As strike rumors circulated in the spring of 1970, community organizations called meetings in disbelief. One HARYOU-ACT notice expressed a common fear, warning that “efforts are being made by the United Federation of Teachers to remove these workers from community control.”48 Paras, led by Velma Murphy Hill, attended these meetings. Although they met with “very hostile” crowds, they “got to tell their side of the story,” promising to continue their community-based work and asking for help in securing their jobs.49

Paras also took to the press. In an article titled “Paraprofessionals Seek Parent Support,” in the New York Amsterdam News, the Harlem para Bessy Canty hoped that “parents [would] understand their plight and support the education aides by keeping their children out of school.” The paper also interviewed Congressman James Scheuer, the sponsor of “New Careers” legislation, who was unequivocally supportive. “We intended this program to provide a ladder from unemployment to paraprofessionalism and on up to professional employment status,” Scheuer explained. “As the program is currently run, the paraprofessionals are being employed on an hourly basis with no job security, no sick leave, no vacation and effectively no chance for upgrading.”50 East Harlem’s El Diario also covered the contract struggle, noting that Puerto Ricans at home would be shocked to learn of the low wages paid to paras by New York City schools.51

While these conversations were taking place in Harlem and East Harlem, the UFT conducted “one of the most intensive internal education campaigns in its history” to convince teachers to support paraprofessionals. It relied on the voices of teachers who worked with paras.52 Eloise Davis, a teacher at PS 108 in Harlem, told the New York Amsterdam News, “Paraprofessionals need and deserve better salaries and benefits.”53 Armed with letters, testimonials, and even a one-act play, teachers from Harlem, the South Bronx, and Central Brooklyn traveled the five boroughs to convince their colleagues to support the contract struggle.54 The board had gambled that teachers would never walk out with paraprofessionals—known to have crossed picket lines in 1968—but at Madison Square Garden in June 1970, teachers voted to strike alongside paras if necessary.

This two-front campaign forced the board to the table that summer. By the fall, paras had won a 140 percent wage increase, health care, and paid time off for teacher training. The New York Amsterdam News, which had excoriated Bayard Rustin for his support of the UFT in 1968, published an op-ed by Rustin titled “Triumph of the Paraprofessionals.” Rustin described the contract as “one of the finest examples of self-determination by the poor.”55 As this phrasing suggested, the paras’ campaign was not an endorsement of the UFT’s leadership. It was an act of self-determination to secure their jobs and legitimate their labor.

Advancing Community-Based Education, 1970–1976

The new decade brought new challenges for community-based educators, but their contract proved a source of empowerment at first. Paras continued their work while taking on new leadership roles in schools and neighborhoods, attending college through their “career ladder” program, and organizing both for and against the UFT’s leadership team. Leaders across the political spectrum also worked to take the “paraprofessional movement” national.

Paraprofessional educators in Harlem returned to a rapidly changing school environment in September 1970 on account of the partial decentralization of the city’s school system.56 Whereas the Central Board of Education retained control over most of the budget and faculty hiring, it transferred management of the Title I funds that supported paraprofessional jobs and hiring decisions about these jobs to thirty-one new Community School Boards. Although sensible on its face, this decision actually centralized paraprofessional programs and undermined smaller units of organization including the PTT clusters and the IS 201 community complex. The uneven decentralization of funds also created incentives for school board members to tear up existing programs, either to put their own visions into practice or to consolidate power and patronage. District 3 (formerly District 5) in Southern Harlem and District 4 in East Harlem preserved many successful programs, but turnover and political infighting in Central Harlem’s District 5 frequently undermined paraprofessional hiring and labor.57

Despite these challenges, Harlem paras continued working for educational equity and community empowerment in their schools and communities, aided by new opportunities for advancement. Georgina Carlo, who had started work in 1967 as a guidance assistant without a high school diploma, earned her GED (general equivalency diploma) and became a college adviser at East Harlem’s Benjamin Franklin High School.58 Her fellow WTC trainee Mercedes Figueroa “organized an anti-narcotics campaign with her neighbors” at IS 201.59 In 1969, District 4’s Community Education Center had launched a program, staffed primarily by paras, to provide materials on Puerto Rican history and culture to classrooms. With continued funding from District 4, the program evolved into El Museo del Barrio.60 Even in District 5, where Superintendent Luther Seabrook blasted the district’s “patronage” hiring in 1975, a “Reading Through Drama” program won praise from evaluators.61 Staffed by paras, the program demonstrated that “students learn best through the process of interaction and communication.”62

Frank Riessman used practices developed in Harlem to create a Career Opportunities Program (COP) that employed and trained nearly fifteen thousand paraprofessional educators across the nation in the 1970s.63 In Harlem, the COP supported paras who worked for Youth Tutoring Youth, a program that trained middle and high school students as reading tutors for younger children, seeking the “double thrust of enriching the young ‘teacher’ as well as the student who has tuned out the message of the structured classroom.”64 At ten schools and public housing community centers in Harlem, paraprofessionals and teachers ran this program, which espoused the goal of involving “parents, indigenous teachers and paraprofessional personnel who have a stake in the community and an emotional investment in the progress of their children.”65 Reviewing the program in 1972, the on-site director, Edward Grant, noted the critical role of paras. They helped select and pair tutors and students, and the fact that paras were “able to empathize” with these students allowed them to “make the tutor aware of the things in his experience which can be used to teach others.”66 A decade after HARYOU responded to “social work colonialism” with “maximum feasible participation,” unionized paraprofessional educators carried this work forward.67

Many Harlem paras became students themselves. Their contract created a Paraprofessional-Teacher Education Program (PTEP) at the City University of New York (CUNY), which educated approximately six thousand paraprofessionals each semester from 1972 through 1976.68 Only a small percentage of paras became teachers; the process took six years, and only about two thousand paras had earned teaching degrees by the time the program was shuttered completely in the early 1980s.69 Nonetheless, the program produced a significant influx of paid training into Harlem and East Harlem and contributed to the integration of the teaching corps.

Paras and their allies also believed educational opportunities inspired paras’ children and students. “Children were proud of their mothers . . . and took a new interest in school work,” noted one WTC report.70 However, Velma Murphy Hill, who received regular letters asking for help enrolling in college, also observed that women attending school was not always easy on their families. She received many requests to “please talk to my husband, he doesn’t want me to go to school.”71 Mercedes Figueroa told her supervisors that her work at IS 201 “raised real problems at home, for her husband was not prepared for his wife to take this sort of career woman, activist role.”72 In the face of deindustrialization and rising unemployment, opportunities for women threatened some men in Harlem families.

Radical Harlem activists looked warily on the process of professionalization. In 1973, Preston Wilcox wrote that professionalization was destroying community-based programs, turning “authentic, natural Black mothers into ‘professional technicians,’ unrelated to the Black community, comfortably subservient to the white community.”73 Nonetheless, Wilcox remained deeply committed to the goal of employing local residents in public schools. He came to the defense of paras whom District 3 barred from participating in PTAs in 1971, writing that “paraprofessionals, who are both ‘poverty parents’ and paid workers in schools are in a unique position to evaluate and monitor programs. Their experience and judgment could be valuable to other parent members.”74 Like Riessman, Wilcox took his vision of parent employment national, creating a “Parent Participation in Follow Through” program that hired “parent stimulators” to assert parent power at seventeen schools in eight states.75

Unionization provided new opportunities for working-class Black and Latina women to take on leadership roles in Harlem and beyond. The UFT paraprofessional chapter led voter registration drives at Harlem schools, hosted weekend conferences on political organizing led by Randolph and Rustin, and helped paras run for local school boards and church committees.76 New York City paras also hit the road to replicate their successful campaign. Led by the tireless Hill, the American Federation of Teachers organized 100,000 paras by 1988.77

Not all paraprofessionals embraced the UFT’s leadership. Some joined with the Teachers Action Caucus (TAC) and other rank-and-file opposition groups to demand a more substantive commitment to community empowerment from their union. The TAC called for the annualization of paraprofessional salaries beginning in 1972, asserting that “paraprofessionals are regular members and an integral part of the school staff . . . the services they perform are essential to the operation of schools.”78 Paras in the TAC challenged New York City’s nascent school-to-prison pipeline and rejected the UFT’s statements on school safety. When its union sought more security officers in schools in 1970, the TAC countered that the board should hire more community-based workers to address conflict between students and teachers.79 In Harlem, the TAC supported a parent boycott in District 4 that demanded “more paraprofessionals,” and it helped develop trainings for paras and teachers in small-group reading in District 3.80

By the time Winifred Tates gave her interview in 1976, paraprofessional educators could look back with pride on a decade of hard-won gains for their schools, communities, and children. Amid the increasingly uncertain political climate of the 1970s, they had reshaped the work of education and created thousands of jobs. However, the city’s 1975 fiscal crisis presented new, existential challenges to their jobs and their work.

Defending Paraprofessional Programs

New York City’s near-bankruptcy in 1975 wreaked havoc on public schools and “disproportionately affected” paraprofessional educators and other Black and Latinx workers, in the words of the deputy schools chancellor Bernard Gifford.81 Harlem’s paras and parents took to the streets in response. The PTAs of PS 76 and PS 144 blocked traffic at 125th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard in July, and PS 76’s UFT chapter joined the protest after learning that their school would lose twenty-five of its forty-three paras. “This is a rip-off of Central Harlem,” said Mrs. Ethel Hughes, the president of PS 144’s PTA. “We are losing the most compared to other areas.” The parent leader Annelle Munn added, “The budget cut is throwing a lot of us out of jobs.”82

Despite these efforts, 5,970 paras, nearly two-thirds of the community-based workforce, had been laid off by the time schools opened in September.83 Union and community support for paraprofessionals had proved complementary in the paras’ 1970 contract campaign, but during the fiscal crisis, UFT seniority provisions put parents and teachers at odds with one another. In January 1976, Harlem parents described these UFT policies as the “destruction of parent power.” If Black educators continued to lose jobs, the group argued, “the images that we have struggled so hard and so long to get for our children will be lost.” The longtime Harlem activist Alice Kornegay noted, “White teachers failed us all these years, and in the last 10 years, Blacks have been coming in and doing the job.”84

The fiscal crisis also gutted the career ladder program. In 1976, CUNY began charging tuition, and funds for paraprofessional training were eliminated from the Board of Education’s budget. Cruelly, the board pushed paraprofessionals who planned to attend classes on summer stipends to apply for unemployment instead.85 Having fought for years to win professional status as educators, paras now found themselves pushed back into the pool of out-of-work Harlemites. The UFT president Albert Shanker attacked the cuts, writing, “We are saving next to nothing, but we are denying the children the services of the paras, we are pushing far into the future the genuine integration of our schools staff, and we are once again needlessly placing people on the treadmill of poverty and welfare.”86 However, immersed in a battle to preserve teacher jobs, the UFT could not preserve the PTEP, even after paraprofessionals picketed union headquarters.87

After the immediate crisis, federal funds from the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act helped rehire many paras. However, the election of Ed Koch as mayor in 1977 presented a new political threat. On the campaign trail, Koch attacked community organizers in Harlem as “poverty pimps.” Once in office, he targeted them for elimination. In the same budget that closed Harlem’s Sydenham Hospital, Koch rejected annual salaries and pension benefits for paraprofessionals in the UFT’s contract, recently adopted from the TAC’s platform.88 Despite pleas from his own schools chancellor, Koch argued that these measures were too expensive and would set a “dangerous” precedent for collective bargaining.89

Paras protested furiously. Velma Hill told the mayor, “You can’t discriminate against one group.” Shelvy Young, a paraprofessional on the Lower East Side, appeared in an advertisement titled “I Love New York, Mayor Koch. Why Doesn’t New York Love Me?” A single mother of two, working full-time and attending school, Young’s composed portrait in the New York Amsterdam News offered a staunch rebuke to Koch’s rhetoric.90 The paper authored an editorial in support of the paras and ran several articles on the fight.91 After arbitration, Koch yielded a small regular summer stipend, but paraprofessionals did not receive pensions until 1983, and then, by an act of state government.92

The Legacy of the Paraprofessional Movement in Harlem

Although paras managed to preserve their jobs, Koch’s attacks set the tone for their marginalization as the 1980s wore on. The mayor deployed racism and sexism to redefine the work of education once again: paras were not educators but “welfare mothers,” their jobs not work but patronage. The New York City schools chancellor Joel Klein would make similar arguments as he attempted to lay off hundreds of paras twenty-five years later.93

Nationally, Ronald Reagan and the Ninety-Seventh Congress radically restructured the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 1982, moving the focus of funding away from community involvement and toward standards and testing. Reagan’s administration disempowered community organizations and undermined public sector unionism, leaving paraprofessionals in Harlem with weakened allies. Shifting paradigms of educational reform that privileged elite outsider perspectives over local knowledge further challenged paraprofessional programs.

Local hiring in Harlem and East Harlem did not simply disappear in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In East Harlem, where stable school board politics and continued federal funding for bilingual education supported paras, their work continued apace. One 1985 study captured the effect of this funding differential on paraprofessional advancement; bilingual paraprofessionals were twice as likely to become teachers.94

After the rise of Koch and Reagan, community-based paras continued to provide instruction, guidance, and outreach in schools, and they do so to this day. However, the transformative potential that paras and their allies had envisioned for this work has been relegated to the margins of school policy and activism. The experiences of community-based educators in Harlem do not offer simple lessons, but their ideas, organizing strategies, and struggles against austerity have much to offer educators today who seek to make the work of education more holistic, communal, and equitable.

To learn more about the topics and themes explored in this chapter, take a look at the reading and teaching resources, timeline, and maps.

| Previous: Chapter 9 | Next: Chapter 11 |

-

Evaluation of Winifred Tates, 1976, Archives of the Women’s Talent Corps, folder 160 (“Student Interviews”), Metropolitan College of New York (hereafter MCNY). ↩︎

-

Chapter 7 in this volume. See also Tamar W. Carroll, Mobilizing New York: AIDS, Antipoverty, and Feminist Activism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015). ↩︎

-

Chapter 9 in this volume. See also Russell Rickford, We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016). ↩︎

-

Alan Gartner and Frank Riessman, “The Paraprofessional Movement in Perspective,” Personnel and Guidance Journal 53, no. 4 (December 1974): 253–56. ↩︎

-

Chapter 11 in this volume. See also Kim Phillips-Fein, Fear City: New York City’s Fiscal Crisis and the Rise of Austerity Politics (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2017). ↩︎

-

William P. Jones, The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights (New York: W. W. Norton, 2014); Michael B. Katz and Mark J. Stern, “The New African-American Inequality” Journal of American History 92, no. 1 (June 2005): 75–108; Wendell Pritchett, Brownsville, Brooklyn: Blacks, Jews, and the Changing Face of the Ghetto (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002); and Brian Purnell, Fighting Jim Crow in the County of Kings: The Congress of Racial Equality in Brooklyn (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013). ↩︎

-

Annelise Orleck and Lisa Gayle Hazirjian, eds., The War on Poverty: A New Grassroots History, 1964–1980 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011), part 2, “Poor Mothers and the War on Poverty,” and especially Adina Back, “‘Parent Power’: Evelina López Antonetty, the United Bronx Parents, and the War on Poverty,” 184-208. ↩︎

-

Christina Collins, “Ethnically Qualified”: Race, Merit, and the Selection of Urban Teachers, 1920–1980 (New York: Teachers College Press, 2011). ↩︎

-

Carroll, Mobilizing New York; and Michael Woodsworth, The Battle for Bed-Stuy: The Long War on Poverty in New York City (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2016). ↩︎

-

“Negro Teachers Form a New Assn. to Aid Harlem Kids,” World-Telegram and Sun, November 11, 1963, Richard Parrish Papers, reel 1, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library (hereafter Schomburg); (hereafter RPP). ↩︎

-

“A Proposal to Establish After School Study Centers In the Central Harlem Area and to Develop New Approaches in the Area of Remediation, Academic Instruction, Guidance, and the Training of Teachers,” reel 3, RPP. ↩︎

-

Meeting, Minutes, April 5, 1963, PS 192, Manhattan, United Federation of Teachers Records, Box 115 Folder 3, Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University (hereafter Tamiment); (hereafter UFTR) ↩︎

-

HARYOU, Youth in the Ghetto: A Study of the Consequences of Powerlessness and a Blueprint for Change (New York; HARYOU, 1964); Laura Pires-Hester, interview with the author, March 9, 2015. On indigeneity as a category for mobilization and analysis in Black communities, see Rickford, We Are an African People and Christopher Emdin, For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood . . . and the Rest of Y’all, Too: Reality Pedagogy and Urban Education (Boston: Beacon Press, 2016). ↩︎

-

Arthur Pearl and Frank Riessman, New Careers for the Poor: The Non-Professional in Human Services (New York: Free Press, 1965). ↩︎

-

Preston Wilcox, “The Controversy at IS 201: One View and a Proposal,” Urban Review, July 1966, Preston Wilcox Papers, box 24, folder 2, Schomburg. ↩︎

-

“Views,” Harlem Parents Committee, April 1966 and September 1967, UFTR, box 87, folder 25. McGeorge Bundy, ed., Reconnection for Learning: A Community School System for New York City Schools (New York, Mayor’s Advisory Panel on Decentralization of New York City Schools, 1967), accessed via ERIC, June 10, 2019. ↩︎

-

On the WTC’s history, see Grace G. Roosevelt, Creating a College That Works: Audrey Cohen and Metropolitan College of New York (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2015). ↩︎

-

Henry M. Brickell et al., An In-Depth Study of Paraprofessionals in District Decentralized ESEA Title I : And New York State Urban Education Projects in the New York City Schools (New York: Institute for Educational Development, 1971). ↩︎

-

By 1967, HARYOU had merged with Associated Community Teams, and became known as HARYOU-ACT. ↩︎

-

“Progress Report 6, March–April 1967,” folder 12, MCNY. ↩︎

-

“1968 Progress Report,” folder 15, MCNY. ↩︎

-

“Progress Report 5, January–February 1967,” folder 11, MCNY. ↩︎

-

Nancy Naples, Grassroots Warriors: Activist Mothering, Community Work, and the War on Poverty (New York: Routledge, 1998), 2–10. Naples builds on the concept of “othermothering” explored by of Patricia Hill Collins in Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment (London: Routledge, 2000). See also Orleck and Hazirjian, War on Poverty. ↩︎

-

Stephanie Gilmore, ed., Feminist Coalitions: Historical Perspectives on Second-Wave Feminism in the United States (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008). In New York, see Carroll, Mobilizing New York and Roberta Gold, When Tenants Claimed the City: The Struggle for Citizenship in New York City Housing (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2014). ↩︎

-

Collins, Black Feminist Thought; Naples, Grassroots Warriors; and Crystal Sanders, A Chance for Change: Head Start and Mississippi’s Black Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016). ↩︎

-

“District Preliminary Proposal, ESEA Title I Project,” Morningside Area Alliance, series 3, box 55, folder 16, Parent Teacher Teams, Columbia University Archives (hereafter MAA) ↩︎

-

“District Preliminary Proposal, ESEA Title I Project,” MAA, series 3, box 55, folder 16. ↩︎

-

“Parents Go Back to School: As Teacher Assistants and TC Students,” TC Week, February 7, 1969, MAA, series 3, box 55, folder 16. ↩︎

-

“Untitled Report, Spring 1968,” MAA, series 3, box 55, folder 16. ↩︎

-

“Untitled Report, Spring 1968,” MAA, series 3, box 55, folder 16. ↩︎

-

“Untitled Report, Spring 1968,” MAA, series 3, box 55, folder 16. ↩︎

-

“Parents Go Back to School: As Teacher Assistants and TC Students,” TC Week, February 7, 1969, MAA, series 3, box 55, folder 16. ↩︎

-

Gladys Roth, “Auxiliary Educational Assistants in New York City Schools,” Internal Report, May 20, 1968, UFTR, box 80, folder 11. ↩︎

-

Roth, “Auxiliary Educational Assistants.” ↩︎

-

“District Preliminary Proposal, ESEA Title I Project,” MAA, series 3, box 55, folder 16. ↩︎

-

Aurelia Greene, interview with the author, August 27, 2014. ↩︎

-

Daniel Perlstein, Justice, Justice: School Politics and the Eclipse of Liberalism (New York: Peter Lang, 2004); Jerald E. Podair, The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2002); and Jonna Perrillo, Uncivil Rights: Teachers, Unions, and Race in the Battle for School Equity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012). ↩︎

-

Letter from Audrey Cohen to David Selden, March 10, 1969, UFTR, box 80, folder 14; and “Second Annual Report and Evaluation, 1967–68,” MCNY, folder 2. ↩︎

-

“Final Report, 1968,” MCNY, folder 2. ↩︎

-

Richard Parrish, “The New York City Teachers Strikes: Blow to Education, Boon to Racism,” Labor Today, RPP, May 1969, reel 1. ↩︎

-

“What Does Control Mean?” Teachers for Community Control Newsletter, December 1968, Anne Filardo Papers on Rank and File Activism in the American Federation of Teachers and in the United Federation of Teachers (TAM 141), Tamiment, box 1, folder 1B, (hereafter AFP). ↩︎

-

Velma Murphy Hill, conversation with the author, April 10, 2014. On the SUNY Downstate Campaign, see Purnell, Fighting Jim Crow. ↩︎

-

Velma Murphy Hill, interview with the author, November 7, 2011. ↩︎

-

Flyer, June 1969, UFTR, box 155, folder 3. ↩︎

-

“Unions Fight to Enlist NY’s Teacher Aides” Baltimore Afro-American, December 27, 1969. ↩︎

-

Collins, “Ethnically Qualified”; Diana D’Amico, “Claiming Profession: The Dynamic Struggle for Teacher Professionalism in the Twentieth Century” (PhD diss., New York University, 2010); and Sonia Song-Ha Lee, Building a Latino Civil Rights Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014). ↩︎

-

Aurelia Greene, interview; Lorraine Montenegro, interview with the author, September 24, 2014. ↩︎

-

“Emergency Meeting Called on School Employment.” New York Amsterdam News, November 29, 1969. ↩︎

-

Velma Murphy Hill, interview. ↩︎

-

“Paraprofessionals Seek Parent Support,” New York Amsterdam News, May 2, 1970. ↩︎

-

Clipping from El Diario, June 15, 1970, UFTR, box 255, folder 2. ↩︎

-

“Internal Report,” 1974, UFTR, box 80, folder 13. ↩︎

-

“Paraprofessionals Seek Parent Support,” New York Amsterdam News, May 2, 1970. ↩︎

-

Newsletter from UFT Chapter Chairman Lucy Shifrin, PS 189K, April 1970, UFTR, box 155, folder 6. ↩︎

-

Bayard Rustin, “Triumph of the Paraprofessionals,” New York Amsterdam News, August 22, 1970. ↩︎

-

Heather Lewis, New York City Public Schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg: Community Control and Its Legacy (New York: Teachers College Press, 2013). ↩︎

-

Heather Lewis, “‘There Is No Board of Education for Harlem’: The I.S. 201 Experimental District and Its Aftermath,” presentation at the Educating Harlem conference, October 2014. ↩︎

-

Student Interviews, MCNY, folder 160. ↩︎

-

Student Interviews, MCNY, folder 160. ↩︎

-

“CSB 3 v. BOE, 1970, Isaiah Robinson Files, Board of Education (BOE), series 378, box 12, folder 12; and El Museo Del Barrio, “History+Timeline,” accessed August 4, 2016. ↩︎

-

“Audit of the District 5 ESEA Programs from 1975–77,” Amelia H. Ashe Files, BOE, series 312, box 61, folder 13. ↩︎

-

“Board of Trustees Community Report, District 5, 1976–1977,” Bernard Gifford Papers, BOE, series 1202, box 4, folder CSD 5 1976–77. ↩︎

-

George Kaplan, From Aide to Teacher: The Story of the Career Opportunities Program (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1977). ↩︎

-

“Youth Tutoring Youth Harlem—East Harlem,” May 27, 1970, BOE, series 1101, box 14, folder 7. ↩︎

-

“Youth Tutoring Youth,” June 7, 1970, BOE, series 1101, box 15, folder 25. ↩︎

-

“Proposal Draft for YTY,” May 18, 1972, BOE, series 1101, box 15, folder 25. ↩︎

-

Chapter 7 in this volume. ↩︎

-

Isaiah Robinson Files, BOE, series 378, box 38, folder 18. ↩︎

-

Collins, “Ethnically Qualified.” ↩︎

-

“Final Report and Evaluation of the Women’s Talent Corps New Careers Program,” 1966–67, MCNY, folder 1. ↩︎

-

UFT Oral History Collection (OH.009), box 1, folder Velma Hill, Tamiment (hereafter UFT OH). ↩︎

-

Student Interviews, MCNY, folder 161. ↩︎

-

“Competencies, Credentialing and the Child Development Associate Program or Maids, Miss Ann and Authentic Mothers,” Schomburg, Preston Wilcox Papers, box 11, folder 17 (hereafter PWP). ↩︎

-

Memo, March 1971, PWP, box 30, folder 3. ↩︎

-

“Continuation Proposal: Parents as Community Developers,” PWP, box 30, folder 2; “The Role of the Local Stimulator,” PWP, box 30, folder 1; and November 23, 1971, Fact Sheet for 9 Afram-Affiliated Sites 1971–72, PWP, box 30, folder 4. ↩︎

-

Velma Murphy Hill, interview. ↩︎

-

AFT PSRP Conference Speech, American Federation of Teachers Records, Office of the President Collection, Albert Shanker Papers, box 65, folder 61, Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University. ↩︎

-

“Support the Paraprofessionals,” December 19, 1972, AFP, box 1, folder 6. ↩︎

-

“TAC Position on Violence,” TAC Newsletter, January 1970, AFP, box 1, folder 4. ↩︎

-

“Viva El Boicot!” TAC Newsletter, December 4, 1972, AFP, box 1, folder 6; and “Let’s Help Our Children Read Better,” District 3 TAC, AFP, February 1, 1973, box 1, folder 6. ↩︎

-

“Thousands of Blacks Facing Loss of Jobs,” New York Amsterdam News, May 7, 1975. See also chapter 11 in this volume. ↩︎

-

“Harlem Takes to the Streets in the Battle of the Budget,” New York Amsterdam News, July 2, 1975. ↩︎

-

“4500 Teachers to Be Laid Off in Month,” New York Times, September 13, 1975. ↩︎

-

“Harlem Parents and Educators Unite for Better Education,” New York Amsterdam News, January 10, 1976. ↩︎

-

Memo to Deputy Chancellor Bernard Gifford and BOE from Frank C. Arricale II, May 28, 1976, Amelia Ashe Files, series 312, box 45, folder 559 Paraprofessionals—Rules and Regulations, BOE. ↩︎

-

“Where We Stand: Some Cuts Are More Stupid Than Others” New York Times, September 19, 1976 (Shanker’s “Where We Stand” column ran as a paid advertisement on Sundays). ↩︎

-

School Board Loses Arbitration on Pact: It Is Told to Pay Paraprofessionals for Training Despite Program’s Removal from City’s Budget,” New York Times, October 29, 1976. ↩︎

-

“Koch’s Budget Unit Urges Closing of 15 Schools, Higher Lunch Fees,” New York Times, January 4, 1979. See also Jonathan Soffer, Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012). ↩︎

-

January 4, 1979, Letter from Ed Koch to Frank Macchiarola, Stephen R. Aiello Files, series 311, box 15, folder 157, BOE. ↩︎

-

“I Love New York, Mayor Koch,” New York Amsterdam News, March 10, 1979. ↩︎

-

“UFT Fights for Salaries,” New York Amsterdam News, September 1, 1979. ↩︎

-

“Cuomo Signs Pension Bills Opposed by Koch as Costly,” New York Times, August 13, 1983. ↩︎

-

Abby Goodnough, “Teacher’s Unions Sues Klein, Claiming Bias in Layoffs of Aides,” New York Times, May 6, 2003. ↩︎

-

Gary D. Goldenback, “Teaching Career Aspirations of Monolingual and Bilingual Paraprofessionals in the New York City School System” (PhD diss, Hofstra University, 1985). ↩︎