Chapter 11. Harlem Schools in the Fiscal Crisis

by Kim Phillips-Fein and Esther Cyna

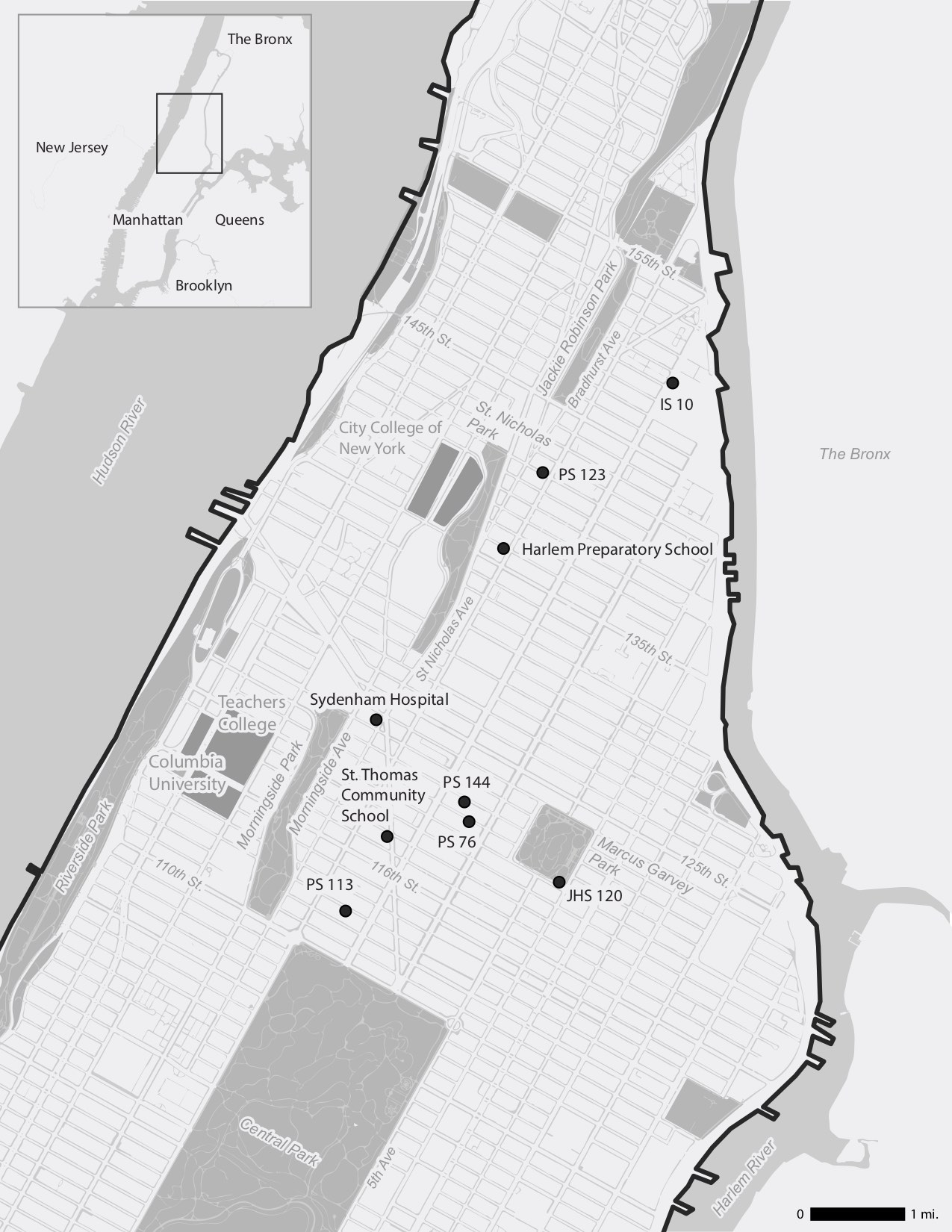

Map design by Rachael Dottle and customized for chapter by Rachel Klepper. Map research by Rachel Klepper. Map layers from: Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, Department of Urban Planning, City of New York; Atlas of the city of New York, borough of Manhattan. From actual surveys and official plans / by George W. and Walter S. Bromley New York Public Library Map Warper; Manhattan Land book of the City of New York. Desk and Library ed. [1956]; New York Public Library Map Warper; and State of New Jersey GIS. Point locations from: School Directories, New York City Board of Education, New York Amsterdam News via ProQuest Historical Newspapers, and multiple archival sources cited in relevant chapters. See maps of the locations discussed in the full volume here.

Many afternoons throughout the spring of 1976, cars and trucks driving across the thoroughfare of 125th Street in Harlem would have found their way blocked by crowds of protesters out for what might have seemed a surprising cause: the protection of neighborhood public schools that the city’s government was threatening to close in order to resolve its ongoing fiscal crisis. One day in March, for example, more than one thousand people participated in a demonstration in support of the local schools.1 On another occasion in April, students, parents, teachers, and school staff marched down the Manhattan artery, bearing signs reading “S.O.S.” and “P.S. 144 must live.” The demonstrators represented two Harlem elementary schools (Public School [PS] 144 and PS 113, both in District 3) that had been slated to shut down as the city made budget cuts to respond to the fiscal shortfall that had brought it to the edge of bankruptcy the previous year. Parents, teachers, students, and staff at the schools swore they would hold an action every single day until September, in order to stop their schools from closing.

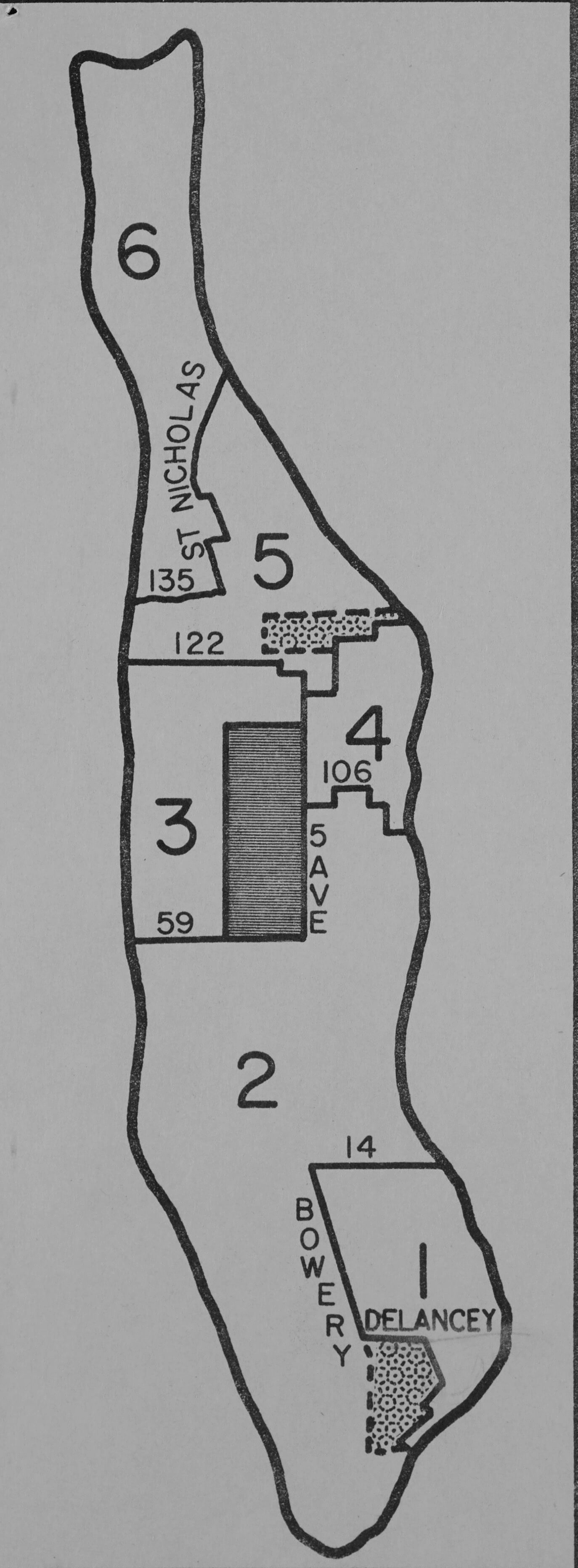

They were right to be concerned. Many schools throughout New York City were threatened with closure in the mid-1970s, but ultimately Harlem would lose more schools than most other neighborhoods in Manhattan.2 In the years after the fiscal crisis that began in 1975, the number of schools in Harlem dropped sharply. District 5—the educational district that consists primarily of Central Harlem—lost eight schools between 1974 and 1983, the largest decline of any of Manhattan’s six districts (figure 11.1). By comparison, only one school in District 3 closed over these years, and two closed in District 1 and District 4 respectively; District 2 and District 6 each added one school, and the number of schools citywide actually grew by five from 981 to 986. Seven of the District 5 schools that closed were elementary schools, and one was a junior high school.3

Figure 11.1 Boundaries of the newly created Community School Districts as of 1970. Source: “Community School District System, Borough of Manhattan,” NYCBOE, Isaiah Robinson Papers, NYCBOE, MA.

The city’s rationale for proposing the “consolidation” of schools was that they were “underutilized,” the number of children attending them having declined sharply as families left the neighborhood. According to the Board of Education, PS 144 was running with 513 students in a building constructed for 1,554, for a 33 percent utilization rate.4 But these definitions of underutilization were not as clear-cut as they might have seemed. Although the city had a strong fiscal incentive to close schools, principals and parents contested the description of schools as underused. They argued that much more of the school space was regularly used than the Board of Education indicated and that the smaller school populations permitted smaller and more intimate classes. Moreover, they suggested that the charge overlooked the central role that these public buildings played in the neighborhood as afterschool centers and community hubs. Schools were not only for educating children—they were visible, public institutions that served as meeting places for various populations and they symbolized the broader commitment of the city to the neighborhood. As the chairperson for the parents’ group that had formed to save the schools put it, public schools often provided the only “viable institution” in the neighborhood: “We don’t have parks, gyms or recreational areas.” In addition, the smaller population attending the schools in the 1970s in fact permitted some relief from the overcrowding that was otherwise the norm. “I can’t understand why the Board would prefer to stuff 32 children into every classroom and force teachers to have to supervise them in ways more reminiscent of a prison than of a school,” Bernice Johnson, the principal of PS 144, told the New York Amsterdam News.5

But there were deeper reasons still for the protests against school closures. The plans to close the schools generated such intense unrest because of the long-standing sense within the neighborhood that Board of Education officials—and the city and state politicians who were pressuring them during the fiscal crisis—knew little of the struggles of Harlem families or their schools. The protesters believed that the mandate for school closures reflected the dictates of administrators who were responding to budgetary pressures and for whom the schools of Harlem were merely an item on the budget line that could easily be crossed off. As one parent participant in the spring protests put it, “What people resent is that the decision is made to close the school arbitrarily by people who have never been here to see what kind of school it is. It makes people angry to have people making decisions who are so far removed.”6 Or as Principal Johnson said, “The Concerned Parents of P.S. 144 and P.S. 113 don’t want these schools closed, and we expect to be out on the streets every day from now on.”7

The New York fiscal crisis of the 1970s has long been recognized as a turning point for the city, a key moment when older traditions of liberal governance were scrapped in favor of a more market-oriented approach.8 Beginning in the spring of 1975, the banks that were accustomed to financing the city government ceased to be willing to market the city’s bonds and notes to investors across the country, citing the mounting debt load and growing expenses that they believed the city government was no longer able to repay. Although Mayor Abraham Beame protested that the banks were treating New York unfairly, that the city simply suffered from cash flow problems, and that it would never actually default, New York ceased to be able to obtain credit. Mayor Beame and Governor Hugh Carey went to Washington to request aid from President Gerald Ford. At first, this was not forthcoming, but at the end of the year, after New York State had essentially obtained control over the city’s budget, Ford agreed to approve legislation that extended loans to New York contingent on the city’s steps toward balancing its budget through steep budget cuts.

The causes of the fiscal crisis and the politics involved in its resolution have been the subject of vigorous historical debate, but the effect of the budget cuts on the daily lives of ordinary New Yorkers has received much less attention.; Still less noted has been the vigorous protest with which many of these cuts were received. The city was roiled by intense division about whether, or to what extent, it was necessary to cut public services to cope with the crisis—and if so which ones should be prioritized. Over the next three years, the number of city workers was reduced by more than sixty thousand as city officials cut the budget under intense pressure from the state and federal governments. The political economy of access to education, knowledge, and culture quickly came to the forefront. Should the city fund these as generously as it had? The City University of New York (CUNY) came in for sharp criticism from President Gerald Ford and others on the right in national politics, who were troubled by New York’s willingness to subsidize a tuition-free university that operated with “open admissions,” guaranteeing access to higher education. There were proposals to consolidate and eliminate CUNY campuses and ultimately to begin charging tuition. Libraries (both branch libraries and the city’s remarkable research libraries) were also threatened with cuts to services and even (in some cases) closure. To some extent, the tensions over the libraries and CUNY reflected ambivalence about the scope of New York’s ambitions: should the city even attempt to run a public university system, or provide extensive library services?

But the crisis also had a profound effect on primary and secondary education, even though operating public schools was widely accepted as well within the normal purview of urban governance. The budget cuts fell with special force on the city’s school system, affecting schools in middle-class and white districts as well as schools serving primarily poor, Black and Latinx children. These cuts were met with widespread protest throughout New York, even as the teachers, school workers, children and families affected sought to adjust to the new reality of reduced funding. Suddenly, the central conflicts that had driven school politics during the 1960s and early 1970s—over community control and racial integration—were joined by a different struggle, focused on adequate funding for education. Throughout New York, parents, teachers and public school advocates found themselves forced to contend with budget cuts that slashed services in the schools and led the school board to propose closing schools.9 The logic for these cuts and closures was enforced by the state agency (the Emergency Financial Control Board) that had been charged with monitoring the city budget and also by the federal government, which mandated cuts in return for fiscal aid. But the way the cuts would be implemented could not help but reflect choices made by the Board of Education—which schools could be treated as expendable, and which ones needed to be saved?

As the fiscal condition of the city bore down on individual schools, the result had the potential to be galvanizing. For neighborhood activists in Harlem, public schools had long represented an investment by the city in the literal future of the neighborhood. The schools were spaces in which people sought to imagine a more egalitarian society for their children and worked to instantiate and embody community values and racial pride. Children’s academic accomplishments were publicized in local newspapers; graduations became occasions for celebration not only for parents and children but for the whole neighborhood. Cuts to the public schools, then, symbolized attacks by the city leadership on community institutions, on the idealism around community control of education that had flourished in the city during the 1960s and early 1970s and finally on the kinds of institutions that had the potential to link poor Harlemites with middle-class people within the neighborhood and the city as a whole. The city’s budget contraction during the fiscal crisis caused great discontent in Harlem for many reasons, among them that African American city workers were far more likely to be laid off than white workers with more seniority as the city downsized, cutting off an important avenue to upward mobility. But its influence on education elicited an unusually powerful response. Many of the people who had been active in other forms of educational activism earlier in the twentieth century began to take up the issues raised by the fiscal crisis because they saw the problems of the neighborhood as intimately linked to the political economy of the city as a whole.10

In Harlem’s District 3 and District 5, the public schools had long been the subject of intense community interest, engagement, and pride as well as frustration and criticism. Early in the 1970s, there was a great deal of energy around education and a sense of the ways that the public schools were failing to serve students as well as the possibilities that education offered for individual and communal uplift. The New York Amsterdam News carried regular reports on education in the neighborhood. The paper printed the names of all honors students at Central Harlem’s District 5 schools in June 1975, reported on the winners of the Benjamin Banneker Mathematics Team Competition (in its second year in 1975), and described innovative school programs such as the Afro-American History Caravan (a mobile classroom that traveled throughout Districts 5 and 6 with the goal of educating African American students about “their history and culture”) and the adult education classes provided by the Board of Education in the evenings.11 Alternative schools such as Harlem Prep (a high school founded by private philanthropists with the goal of graduating high school dropouts and enabling them to gain college admission—admission to college was initially the criterion for graduation) also received regular coverage in the Amsterdam News.12 “The salvation of our community, our city, our nation, our world is basically dependent on how well all adults educate the children to a responsible way of life,” read one article reporting on St. Thomas Community School (an independent K–8 program).13 Early in 1975, the Amsterdam News also ran an article by the public relations staff for District 5, claiming that it had “made considerable progress” toward resolving its long-standing problems: there were no more patronage or “no-show” jobs in the district, reading scores were climbing slightly, and active efforts were under way to improve the schools with federal funds for a math lab, bilingual programming, and antidrug efforts.14

Such recognition, praise, and tentative hopes for the schools coexisted with deep anxieties about their limitations as well as complaints and unhappiness about low test scores and the myriad barriers to student achievement. Often, parents were criticized for the problems of education in the neighborhood. The New York Amsterdam News regularly published letters from readers who castigated parents for failing to be more deeply involved with the schools.15

For a neighborhood so concerned with education, the fiscal crisis seemed a disaster. The budget cuts that followed the fiscal crisis affected the entire spectrum of city services, but they had an especially deep impact on education. The number of people employed by the Board of Education fell by almost 20 percent between 1975 and 1978, meaning that the schools employed thousands fewer teachers, not to mention guidance counselors and other support staff. Class sizes grew, art and extracurricular programs were cut back, basic maintenance and security were reduced, and the school day was shortened by ninety minutes. School crossing guards throughout the city were laid off. The budget for school athletics shrank by $1 million (from $2.5 million) with the result that twenty thousand fewer students could play and participate.16

The devastation was such that it met with a legislative response. In 1976, the state senators Leonard Stavisky and Roy Goodman (the latter a liberal Republican) proposed legislation that would bar the city from cutting education funding too rapidly as it sought to meet the terms of the fiscal crisis. Despite opposition from both Governor Hugh Carey and Mayor Abraham Beame (who argued that it would limit the city’s ability to respond to the crisis), the legislation passed, and was then upheld by the legislature over Carey’s veto.17 But the cuts had already transformed the nature of the public schools in the city, making them schools of last resort for poor people, increasingly unattractive to middle-class families. One op-ed in the New York Times, written by a mother who had chosen to take her young daughter out of a public school and enroll her in a private one, bemoaned the changes: “New York is forcing middle-class children out of its schools and providing precious little education to those that remain.”18

As soon as the depth of the fiscal crisis became evident and the likelihood of steep budget cuts clear, a strenuous community response began to build in Harlem. Education was not the only subject of concern. Neighborhood residents feared the loss of health institutions such as Sydenham Hospital, a historically African American hospital that earlier in the twentieth century had been one of the few places Black doctors could practice.19 The Morningside Health Center, a neighborhood health center focused on women’s health and prenatal care that served many young mothers in upper Manhattan, was threatened with closure.20 Harlem Hospital announced in 1975 that it would close its School of Nursing.21 All these cuts affected a population that had been in need of more health services before the fiscal crisis had even begun. In an announcement of a series of forums on the effect of the fiscal crisis on African American and Latinx New Yorkers, State Assemblyman Albert Vann articulated the problem well: “No one has really dealt with communities such as ours which were suffering from a lack of services before the fiscal crisis.”22

There was a widespread sense that the threatened cuts should be met with forceful political resistance. African American legislators and community group leaders organized a voter registration drive for late August 1975 in an attempt to add 100,000 Black New Yorkers to the rolls in order to provide a form of “neighborhood protection from closing schools, firing teachers, closing hospitals, massive lay-offs and the curtailment of vital community services,” as the New York Amsterdam News put it.23 Many in Harlem were concerned that Black workers would be the first laid off from their jobs with the city government (jobs that had only recently become more secure avenues to middle-class status) because they had less seniority in union positions. The sense that the effects of the budget cuts would be felt most profoundly by poor African American and Latinx communities was augmented by the suggestion of Roger Starr, the city’s deputy housing administrator, that New York should pursue a policy of “planned shrinkage”—strategically targeting its cuts to parts of the city that it would simply cease to fund or care for, essentially to let go. Neighborhoods that were losing population should no longer have subway service, fire protection, health care, and schools, which would eventually stimulate more people still to leave altogether. Starr’s comments were met with outrage from city and state legislators and decried by others in the Beame administration. The city never formally adopted such a policy; instead, Starr left his position in city government. But from the perspective of affected communities, Starr’s writing crystallized what many believed was the city’s underlying attitude—a logic of neglect and disregard. “Fiscal Cuts—Or Racial Cuts?” asked one New York Amsterdam News editorial headline, criticizing the proposal to close several campuses in the CUNY system that served predominantly nonwhite students, including Hostos Community College in the South Bronx, and to turn other four-year colleges (such as Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn) into two-year schools.24

For all these varied concerns, fears about the effects of the fiscal crisis focused especially on schools. As soon as the magnitude of the cuts became clear in the summer of 1975, Deputy Chancellor Bernard Gifford warned that the school layoffs mandated by Mayor Beame would “fall disproportionately upon the shoulders of Blacks and Puerto Ricans.” The New York Amsterdam News called on the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) and the city to adopt “a plan for all of us” that would avoid any pattern of discriminatory layoffs, especially in education—urging the UFT to give up on cost-of-living increases in order to reduce the number of teachers who had to lose their jobs. (This was a position the UFT would reject, instead choosing to prioritize teacher salaries.)25 Such anxieties about the effects of cuts on minority teachers were justified. The federal Civil Rights Office of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare issued a 1976 report criticizing New York’s Board of Education for its racially discriminatory practices—which had resulted in one of the lowest proportions of minority teachers in the country, only about 14 percent even after ten years of concerted effort to hire more African American teachers. This proportion did not decrease in the years after the crisis, as Gifford feared. But any progress that had taken place slowed to a standstill.26

In addition to the anxiety that the teaching staff of schools would become whiter as Black and Latinx teachers lost their jobs, parents were also afraid that the cuts would endanger the quality of education for students in schools that already had to grapple with many challenges. They quickly organized to meet the cuts with protests. Along with representatives of community groups, parents started the Harlem and East Harlem Coalition to Prevent the Closing of Schools.27 Early in July 1975, the parent-teacher associations from PS 76 on West 121st Street and PS 144 on West 122nd Street organized protests that blocked traffic on 125th Street to protest the loss of paraprofessionals, teachers, and especially corrective reading and math teachers at their schools. Some prekindergarten and kindergarten classes would be eliminated entirely. Class sizes would increase to as many as forty-nine students with one teacher and no assistants. All these cuts took place against the backdrop of existing deprivation: as the head of the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) at 144 said, “Our children are at least two years behind and we are losing the remedial reading program.”28

Protests continued as the cuts went into effect. In the fall of 1976, students at the Frederick Douglass School (Intermediate School [IS] 10, a middle school located at Seventh Avenue and 149th Street) boycotted the school when they found that twelve teachers had been laid off with no replacements, leaving ten classrooms with no teachers at all in subjects such as social studies, English, science, and math, which students needed in order to pass the upcoming Regents exams.29 Wadleigh Intermediate School in the early 1970s held an annual Black Solidarity Day on November 1, a one-day boycott of school by students, teachers, and staff, in recognition of “unity, love, peace and our common desire for a better community in which to live.” In 1976, the president of the Parent-Teacher Association called for Black Solidarity Day to be dedicated as a “day of mourning” for “the death of public education in New York City, brought about by crippling budget cuts and layoffs.” Such efforts were not the work of a fringe group of parents. The principal, Elfreda S. Wright, approved the action.30

Whatever effects such demonstrations may have had in particular cases, they were not adequate to prevent or slow the cuts across the board. District 3, for example, lost about 19 percent of its tax levy budget between 1975 and 1977. This meant that the number of elementary school teachers fell from 644 to 432, and junior high school teachers declined from 295 to 224.31 The situation that prevailed in many public schools after such cuts was bleak—even more so than before the fiscal crisis. In March 1976, Board of Education officials visited one District 5 school—PS 123, a K–5 elementary school on West 140th Street—and described some of the difficulties. The school, with about 800 students, all of whom qualified for free lunch, had lost about half of its teaching staff over the fiscal crisis, going from 60 in 1974–75 to 30 in 1975–76. The number of paraprofessionals had declined from 11 to 7, a guidance counselor was present only one day a week, and there was one assistant principal in addition to the acting principal. The principal—who had served at the school for four years—believed that teachers were being excessed from “ghetto areas” and reassigned to more affluent ones. In their notes on the visit, the Board of Education representatives described “a general pattern of chaos” in the building near dismissal time, as children roamed the halls with little supervision, roughhousing and playing in ways that appeared dangerous—in front of a broken stained glass window, for example. There was no playground, and the principal had little interest in trying to take students to one in the neighborhood, saying they played too much already. Most depressing of all was the low morale. Although the principal blamed a “lack of responsibility” on the part of either teachers or students, he had little sense of anything that might improve the situation. He seemed, the observers noted, “most despondent over the progress of the children in his school,” and he feared that they would not be able to overcome “a system which is stacked against them.”32

Although the school cuts did impact middle-class schools as well as those serving poor people, many of the programs most affected were those that involved those most desperately in need. For example, the city wanted to close the five schools that it had operated for high school girls who became pregnant, which had served as a supportive space for students who were otherwise at greater-than-usual risk of leaving school altogether. “While we recognize that cuts have to be made, the total dismantling of such a program is a crime for it leaves 2,000 students out on the streets making them an even greater burden on society,” one irate reader wrote to the New York Amsterdam News.33 (Four teenagers organized a protest at City Hall, standing with their backs to television cameras. In 1978, the schools received funding extensions enabling them to remain open.)34 Adult education centers also lost much of their funding—cuts that were borne especially by poor Black and Latinx neighborhoods, where the centers were less likely to be able to access alternative sources of money.35 In some cases, the city had been supporting the schools with its most financially risky decisions, such as borrowing through the capital budget to pay for vocational schools or textbooks. Once this source of funding disappeared as the city cleaned up its accounting, it was far from clear where the money could be made up.

For some parents, the dangers to the public school system and the effect that budget cuts would have on the quality of education seemed sufficiently grave that they grew pessimistic about the chances that public education could offer their children. They began to press for alternatives, especially in the form of vouchers giving them state funds that could be transferred to private schools or new independent schools founded by concerned parents. By the fall of 1975, the Harlem Parents Union—a group representing parents with children in Districts 4, 5, 7, and 9—began to petition the state for school vouchers to enable them to send their children to private schools or to found new parent-run schools as alternatives to the public system. Parents with children in failing schools should be able to gain the funds that would go to those schools and seek out other routes to education. Some families kept their children home from school to boycott the “educational deprivation for Black and Spanish-speaking children in New York City,” as a letter from the Citizens Committee for Effective Education (another parent-run organization) read.36 People in the neighborhood looked to Brooklyn, where the Timothy Baptist Church opened its own school as an alternative to the public schools because of the latter’s “failure” to provide “care, respect and quality education” for African American students.37 Black parents on the Lower East Side who opened a private school also received positive mention.

But for other parents, the crisis became a chance to try to defend the public system, drawing on the long traditions within the neighborhood of fighting for better school buildings and improved education in general. This emerged most dramatically when schools were threatened not just with cutbacks, but with closure. The logic behind closing schools was simple. The population of Harlem was declining over the 1970s, and as a result the Board of Education argued that the neighborhood no longer needed as many schools. The board claimed that taken as a whole District 5 was failing to use 8,008 seats on the elementary school level and 2,537 on the middle school level. Its buildings were regularly not filled to capacity, or even close—they often enrolled less than half the students they could fit.38 The answer, as the board saw it, was to close and consolidate Harlem’s schools. Yet despite the widespread awareness of the many problems with the schools—problems only exacerbated by the funding cuts—neighborhood residents were still deeply troubled about plans that involved school closings or consolidation. This issue resonated with long-standing struggles over keeping schools within the neighborhood open, going back to the earlier conflicts over Wadleigh High School for Girls, which had been threatened with closure during the 1930s and then turned into a coeducational junior high school, thus depriving the neighborhood of its lone high school.

Street protests were one means by which to protect the schools. Filing appeals regarding school closures was another. The Community School Board (CSB) for Harlem’s District 5 was a troubled institution, wracked with internal conflicts and rife with charges of nepotism and political patronage. However, it also briefly emerged in the mid-1970s as a protector of the schools in the district that were threatened with closure. In the summer of 1976, as the Board of Education sought to bring the budget into balance through school consolidation, the CSB filed a series of legal appeals of the board’s decisions to close schools.

One of the most intense of these conflicts dealt with the board’s decision to close Junior High School (JHS) 120—an alternative, unzoned junior high school with 665 children, operating in a building with a capacity of 1,515. JHS 120 had been one of the Harlem junior high schools that parents in the neighborhood had boycotted in 1958, saying that conditions at the school were substandard and refusing to send their children there. When the Board of Education brought the parents to court for keeping their children home, Judge Justine Polier instead charged the city with failing to provide the city’s African American children with an adequate education.39

In 1976, however, parents sought to protect the very existence of JHS 120. The board wanted to close the school, saying that it was too underenrolled to keep open and that a new junior high school was set to open in the district anyway, which would further reduce the school population. In its appeal, the CSB argued that the school had special qualities that justified keeping it open. The school had excelled in a borough-wide mathematics competition. It had a unique curriculum focused on math and science. Most of all, the “financial and emotional hardships imposed upon children and parents of changing teachers, schools and locations could prove devastating.”40 The PTA for JHS 120 sent an additional letter, emphasizing that the school had a special math and science orientation, that sixty-three students had recently gained admission to specialized high schools that had entrance exams, and, in a reference to the unzoned nature of the school, which meant that parents had to specifically seek it out, observing that “parents chose this school for their children because of the special emphasis on mathematics and science.” Speaking of her ambitions for the school, the president of the PTA wrote of her dream “to make Junior High School 120 an educational showcase, an ‘Ivy League’ junior high school within the geographic boundaries of Harlem.”41 Students at JHS 120 joined the fight, protesting and blocking traffic outside of their school in September 1976.42

Rather than close JHS 120, the Community School Board proposed closing an elementary school, PS 79, which had only 171 students. These students could be moved to JHS 120, which would then house two schools, one elementary and one middle school, helping the building to be more fully utilized.43 (It should be noted that the parents at PS 79 strongly objected to this idea, and their PTA contacted the board as well to say that they had not been part of any discussions about closing the school.)44

The Board of Education was skeptical of the Community School Board’s appeals. “I am in total agreement with your statement that the original decision to close these schools was correct and that the local board has yielded to political pressure in appealing,” one Board of Education member wrote to Isaiah Robinson, the president of the board (and himself formerly a Harlem parent activist).45 Although in other circumstances “smaller programs, more space for support services and special projects” might be priorities of the board as well as parents and Community School Boards, the fiscal crisis made this impossible. The Appeal Board of the Board of Education rejected the petition: “The school system now is faced with extensive and irrevocable cutbacks which necessitate economies in essential services.”46 The Community School Board continued to appeal the closure of JHS 120, attempting to bring a petition in New York State Supreme Court to challenge the closure. This, however, was also dismissed: the court ruled that the board had the power and the right to make the decision to close the school and that there was no justification for abrogating that in this instance.47 In the end, JHS 120 was closed.

Community School Board 5 also clashed with the central board regarding its school guards. The board had ordered the district to lay off its school guards as it sought to comply with the budget reductions. Layoffs of guards were especially contentious—the New York Amsterdam News had reported on rising crime in the city’s schools following the reduction in the number of guards.48 District 5 refused to fire the nineteen guards employed by the district, and sought to reorganize funds in order to keep them on staff. The Board of Education wrote to the district superintendent, Luther Seabrook, to threaten the school district with “criminal liability” for failing to comply with the Emergency Financial Control Act.49 “May I remind you that we have cut our services to children far beyond comparable cuts in other districts,” Seabrook responded, arguing that the guards were necessary to maintain the safety of staff, students, and faculty.50 He proposed other methods of saving money, including closing the District Office altogether during the month of July.51 The board rejected this idea. Ultimately, angry that the local board had tried to keep hiring guards despite the directive to lay them off, the board attempted to freeze payments to the guards for work they had already done, although they relented on this position under pressure from the guards union.52

The tense relationships between the District 5 Community School Board and the central Board of Education came to a head when the latter decided to suspend the local school board. There were intense divisions within the CSB (centered, in part, on the Board of Education’s dismissal of Seabrook, a very popular African American superintendent, in the late spring of 1976, a decision that led to a widespread outcry in the neighborhood culminating in the occupation of the CSB offices by supporters of Seabrook) as well as many allegations of overall disorganization, malfeasance, and poor administration.53 However, the fiscal crisis and the difficulty that CSB 5 faced in complying with the new mandates also played a role in the suspension. In July 1976, Deputy Chancellor Gifford recommended this course of action, warning that the CSB was projected to overspend its tax levy budget by $400,000, and that even as the central Board of Education ordered the school districts to reduce expenditures, the CSB had ordered the superintendent for District 5 to “‘immediately rehire [terminated] neighborhood workers.’” Citing “fiscal responsibility” and the “legal mandate” of the Community School Board to carry out the policies of the Board of Education, Gifford recommended that the entire CSB be suspended and replaced “until such time as it is clear that the required fiscal controls and stability are firmly established in the district.”54 In October 1976, Chancellor Irving Anker followed through on the threat, citing the failure of the CSB to “excess” sufficient numbers of teachers (the school district had continued to employ about fifty teachers it was supposed to lay off) as evidence of the failure of the CSB to “comply with its duties under law.”55 The board members appealed, but to no avail. CSB 5 was undeniably plagued by long-standing fiscal and organizational problems, but the conflict is also notable because of the context of retrenchment that ultimately justified the takeover.

The fiscal crisis of the 1970s raised a host of new difficulties for Harlem’s schools. In a neighborhood already short on resources and already facing such extensive needs, the fiscal crisis meant further cutbacks and greater instability in neighborhood institutions that had previously been unable to fully deliver on their promises. The result was the decline of any confidence whatsoever in public schools. Even when threatened cuts were rescinded, the experience taught that it was difficult to rely on public institutions. Before the fiscal crisis, educational activism in Harlem had often focused on issues of racial justice in the public schools, as well as the relationship between the central Board of Education and the quest of the neighborhood for greater community control. The fiscal crisis revealed a different aspect of this politics, as critics of the public schools were suddenly forced to defend their very existence. The myriad protests to keep Harlem schools from closing helped to determine which schools could be closed, but it did not address the larger problem of the lack of resources. As a result, the mobilization within the neighborhood—like much activism during the fiscal crisis moment—was limited: it could protest closures and cuts, but the questions about racial equality and local democracy that had animated Harlem’s schools earlier in the century were unable to occupy the same space. The result, in some cases, was declining faith in the potential of the public system, which helped pave the way for the rise of charter schools.

However, the community school boards (despite their flaws) and the rich history of school-related protests in the neighborhood also helped to mobilize opposition to budget cuts during the fiscal crisis. The people who blocked traffic on 125th Street in the spring of 1976 did so out of an insistent faith that the schools and children of Harlem were not hopeless and should not be abandoned, that there remained much within them worthy of salvage and transformation.

To learn more about the topics and themes explored in this chapter, take a look at the reading and teaching resources, timeline, and maps.

| Previous: Chapter 10 | Next: Chapter 12 |

-

George Goodman Jr., “Planned Closing of P.S. 144 Protested,” New York Times, March 12, 1976, 37. ↩︎

-

Some reports suggested that the city was planning at the outset to close about fifty schools. “Schools Proposed for Consolidation,” Amelia Ashe Papers, box 82, folder 24–8, “School Closing Procedures,” Board of Education Papers, Municipal Archives (hereafter AAP). It is difficult to identify a master list of all schools that the city initially planned to close during the 1970s, and newspaper reports conflict as well; what is striking is how many of the schools that ultimately did close were Harlem schools. ↩︎

-

Community and High Schools Profiles, 1974–1975; and Community and High Schools Profiles, 1983–1984. These reports are available at the City Library. ↩︎

-

Community and High Schools Profiles, 1974–1975; and Community and High Schools Profiles, 1983–1984. ↩︎

-

Carlos V. Ortiz, “School Protesters Block Harlem Traffic,” New York Amsterdam News, April 3, 1976, A10; and Robert Collazo, “PS 113 Vow to Keep School Open,” New York Amsterdam News, February 14, 1976, C9. ↩︎

-

Goodman, “Planned Closing of P.S. 144 Protested.” ↩︎

-

Ortiz, “School Protesters Block Harlem Traffic”; and Collazo, “PS 113 Vow to Keep School Open.” ↩︎

-

Analysis throughout this article draws on coauthor Kim Phillips-Fein’s book on the fiscal crisis, Fear City: New York’s Fiscal Crisis and the Rise of Austerity Politics (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2017). For earlier scholarship on the fiscal crisis, see, for example, Martin Shefter, Political Crisis/Fiscal Crisis: The Collapse and Revival of New York City (New York: Basic Books, 1985); Ester Fuchs, Mayors and Money: Fiscal Policy in New York and Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992); Raymond Horton and Charles Brecher with Robert A. Cropf and Dean Michael Mead, Power Failure: New York City Power and Politics Since 1960 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); and John Mollenkopf, A Phoenix in the Ashes: The Rise and Fall of the Koch Coalition in New York City Politics (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994). Joshua A. Freeman, Working Class New York: Life and Labor Since World War II (New York: New Press, 2000), 256-290, remains the best single chapter (“The Fiscal Crisis”) on the politics of the fiscal crisis, and William Tabb, The Long Default: New York City and the Urban Fiscal Crisis (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1982) provides a survey of the budget cuts. Little has been written specifically on the schools in the fiscal crisis, other than Lynne A. Weikart, “Decision Making and the Impact of Those Decisions During New York City’s Fiscal Crisis in the Public Schools, 1975–77” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1984). ↩︎

-

Farnsworth Fowle, “East Harlem School Facing End,” New York Times, June 15, 1976, 40. According to this article, the number of schools to be closed was thirty-seven, for savings of $5 million. ↩︎

-

Although scholars of education have recognized the narrowed budgets that urban districts faced in the 1960s and 1970s, many have treated these as the product of falling property tax bases via deindustrialization, and weakening will to support public education alongside rising student need. See, for example, the treatments of the 1960s and 1970s in classic works of urban educational history, including David Tyack, The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1974) and Jeffrey Mirel, The Rise and Fall of an Urban School System: Detroit (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988). This chapter goes beyond these more general treatments to interrogate the ways that political organizing and the distribution of political power determined how city budget conditions would shape education policy choices. ↩︎

-

“June Is Graduation Time When Scholastic Honors Are Being Passed Out,” New York Amsterdam News, June 25, 1975, C11; “School District 5 Math Team Winners,” New York Amsterdam News, March 8, 1976, B8; “Harlem Classroom on Wheels,” New York Amsterdam News, March 8, 1976, A5; and “New Kind of Success Story . . .” New York Amsterdam News, May 7, 1975, B8. ↩︎

-

Harlem Prep affiliated with the Board of Education in 1974. For more on its history, see Barry M. Goldenberg, “The Story of Harlem Prep: Cultivating a Community School in New York City,” Gotham: A Blog for Scholars, August 2, 2016. ↩︎

-

“Parents, Teachers Work Together at St. Thomas Community School,” New York Amsterdam News, November 12, 1976, B8. ↩︎

-

Public Relations Staff, District 5, “District 5 Moves Forward,” New York Amsterdam News, February 22, 1975, B3. That this article was by a District 5 staff member may be a reason to treat its claims with skepticism, but the decision of the paper to print it reflects the intense desire in the community to see improvement in District 5. ↩︎

-

“Letter of Week,” New York Amsterdam News, March 22, 1975, A4. ↩︎

-

“City School Athletic Cuts Hurt Blacks,” New York Amsterdam News, September 5, 1975, B1. ↩︎

-

Robert W. Bailey, The Crisis Regime: The MAC, the EFCB, and the Political Impact of the New York City Financial Crisis (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985), 100–103. See also Phillips-Fein, Fear City, 220–223. ↩︎

-

Betsy Haggerty, “Kate Isn’t In P.S. 87: Here’s Why,” New York Times, October 19, 1976, 39. ↩︎

-

J. Zamgba Browne, “Harlemites Vow to Keep Sydenham Open,” New York Amsterdam News, April 3, 1976, A1. ↩︎

-

“Morningside Health Center in Jeopardy of Closing: Funds to Stop,” New York Amsterdam News, March 1, 1975, C12. ↩︎

-

Victor O. Koroji, “Harlem Hospital School of Nursing Facing Shutdown,” New York Amsterdam News, July 23, 1975, A1. ↩︎

-

“Set Community Forums on NYC Fiscal Crisis,” New York Amsterdam News, January 10, 1976, B2. ↩︎

-

“Political Group Formed to Register 100,000 Blacks,” New York Amsterdam News, August 6, 1975, A1. ↩︎

-

“Fiscal Cuts—Or Racial Cuts?” New York Amsterdam News, February 28, 1976, A4. ↩︎

-

“Thousands of Blacks Facing Loss of Jobs,” New York Amsterdam News, May 7, 1975, A1. See also “A Fair Solution,” New York Amsterdam News, September 4, 1976, A4. ↩︎

-

Weikart, “Decision Making,” 167. ↩︎

-

John O’Neill of the Community Development Agency at the Human Resources Administration to Bernard Gifford, May 5, 1976, Bernard Gifford Papers, series 1201, box 2, folder “CSD 5, 1975–1976,” Board of Education of the City of New York Collection, Municipal Archives of the City of New York (BOE MA); (hereafter BGP). ↩︎

-

Simon Anekwe, “Harlem Takes to the Streets in the Battle of the Budget,” New York Amsterdam News, July 2, 1975, A7. ↩︎

-

Simon Anekwe, “Threaten School Boycott at IS 10,” New York Amsterdam News, October 16, 1976, A1. ↩︎

-

Wadleigh High School Collection, box 4, file 10, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. ↩︎

-

Weikart, “Decision Making,” 190. Weikert looked closely at three CSDs, District 3 being one of them. ↩︎

-

“Notes on School Visit—March 4, 1976,” Visited by Amelia Ashe—Bob Hanlon—School: P.S. 123, at CSB 5. AAP, box 61, folder 11. ↩︎

-

Ruby S. Hill, “Schools for Pregnant Girls,” New York Amsterdam News, September 23, 1976, A4. ↩︎

-

Edward Ranzal, “Schools Closing, Pregnant Girls Stage a Protest,” New York Times, October 16, 1976, 29; and David Vidal, “Extension Granted 5 Special Schools for Pregnant Girls,” New York Times, January 22, 1977, 20. ↩︎

-

Ralph R. Reuter to Stephen Aiello, February 21, 1978. Stephen R. Aiello Files, Box 1, Folder 2, “Adult Education, 1978-1979.” New York City Municipal Archives. Reuter was the chairman of the advisory council of the Office of Continuing Education. In this letter to the president of the Board of Education, he reported that many centers in poor neighborhoods had been closed down—in Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, the South Bronx—but wealthier centers had been kept open. ↩︎

-

Simon Anekwe, “Black Parents Seek State Funds for Private Schools,” New York Amsterdam News, October 8, 1975, 20. ↩︎

-

J. Zamgba Browne, “Church Takes Lead in Education: Opens an Alternative School,” New York Amsterdam News, December 4, 1976, A11. ↩︎

-

Board of Education of the City of New York in the Matter of the Appeal of Community School Board No. 5. AAP, box 83, folder 25A. ↩︎

-

See Adina Back, “Exposing the ‘Whole Segregation Myth’: The Harlem Nine and New York City’s Desegregation Battles,” in Freedom North: Black Freedom Struggles Outside the South, 1940–1980, ed. Jeanne Theoharis and Kozomi Woodard (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 65–93. ↩︎

-

Delia Ortiz to Harold Siegel, May 14, 1976, AAP, box 82, folder 251. ↩︎

-

From Mrs. Delores Green, P.T.A. President. The version of the letter in the Ashe papers is addressed to Charles Gadsen, but the letter appears to have been Xeroxed and was likely sent to several different officials. May 3, 1976, AAP, box 82, folder 251. ↩︎

-

“Harlem School Fight,” New York Amsterdam News, September 25, 1976, C12. ↩︎

-

Delia Ortiz to Amelia Ashe, June 22, 1976, AAP, box 82, folder 251. ↩︎

-

The Parents Association of PS 79 Manhattan, John Haigley-Bey, President, to Amelia Ashe, June 24, 1976, AAP, box 82, folder 251. ↩︎

-

Amelia Ashe to Isaiah Robinson, June 18, 1976, AAP, box 82, folder 251. ↩︎

-

In the Matter of the Appeal of Community School Board 5 from the Actions of the Chancellor in Regard to the Closing of J-120-M, AAP, box 82, folder 251. ↩︎

-

Memorandum of the Supreme Court of Kings County, in the matter of the Application of Delores Green vs. Board of Education of the City of New York et al., September 24, 1976, AAP, box 82, folder 251. ↩︎

-

Les Mathews, “Guards Are Laid Off, Crime Rate Increases,” New York Amsterdam News, March 27, 1976, A12. ↩︎

-

Alfredo Mathew to Luther Seabrook and the Chairman and Members of CSB 5, April 5, 1976, BGP, box 1202, folder CSD 5, 1975–1976. ↩︎

-

Luther Seabrook to Bernard Gifford, April 26, 1976, BGP, box 2, folder CSD 5, 1975–1976. Seabrook wrote Gifford after the checks to pay the guards were held up at the Board of Education. “I do not seek confrontation; I do not seek special favors,” he wrote. “I do expect equitable treatment, regardless of the ‘alleged’ powerlessness of my community. Please see that those checks are not held up on April 28th.” ↩︎

-

Luther Seabrook to Irving Anker, March 22, 1976, BGP, box 2, folder CSD 5, 1975–1976, BOE MA. ↩︎

-

Frank Scarpinato to Irving Anker, April 28, 1975, BGP, box 2, folder CSD 5, 1975–1976. ↩︎

-

For some discussion of the many other issues in CSB 5, and the board’s response to them, see letter from the CSB Board members to Bernard Gifford, June 30, 1976, AAP, box 61, folder 12. This letter is not signed but it appears to be from CSB 5 board members, following a meeting with Gifford. Also worth noting is a letter from February 1976 signed by half the school board, appealing to Anker to take action against the other half; see John Davis, Louise Gaithner, Charles Gadsen, and John Hicks to Irving Anker, February 2, 1976, BGP, box 2, folder CSD 5, 1975–1976. Finally, see the letter from Marjorie Lewis, Charles Gadsen, Delia Ortiz, and Bernice Bolar to the Board of Education, November 8, 1976, appealing the suspension, AAP, box 61, folder 12. ↩︎

-

Bernard Gifford to the members of Community School Board 5, July 20, 1976, AAP, box 61, folder 12. ↩︎

-

Irving Anker to the members of Community School Board 5, October 26, 1976, AAP, box 61, folder 12. ↩︎