Chapter 12. Pursuing “Real Power to Parents”: Babette Edwards’s Activism from Community Control to Charter Schools

by Brittney Lewer

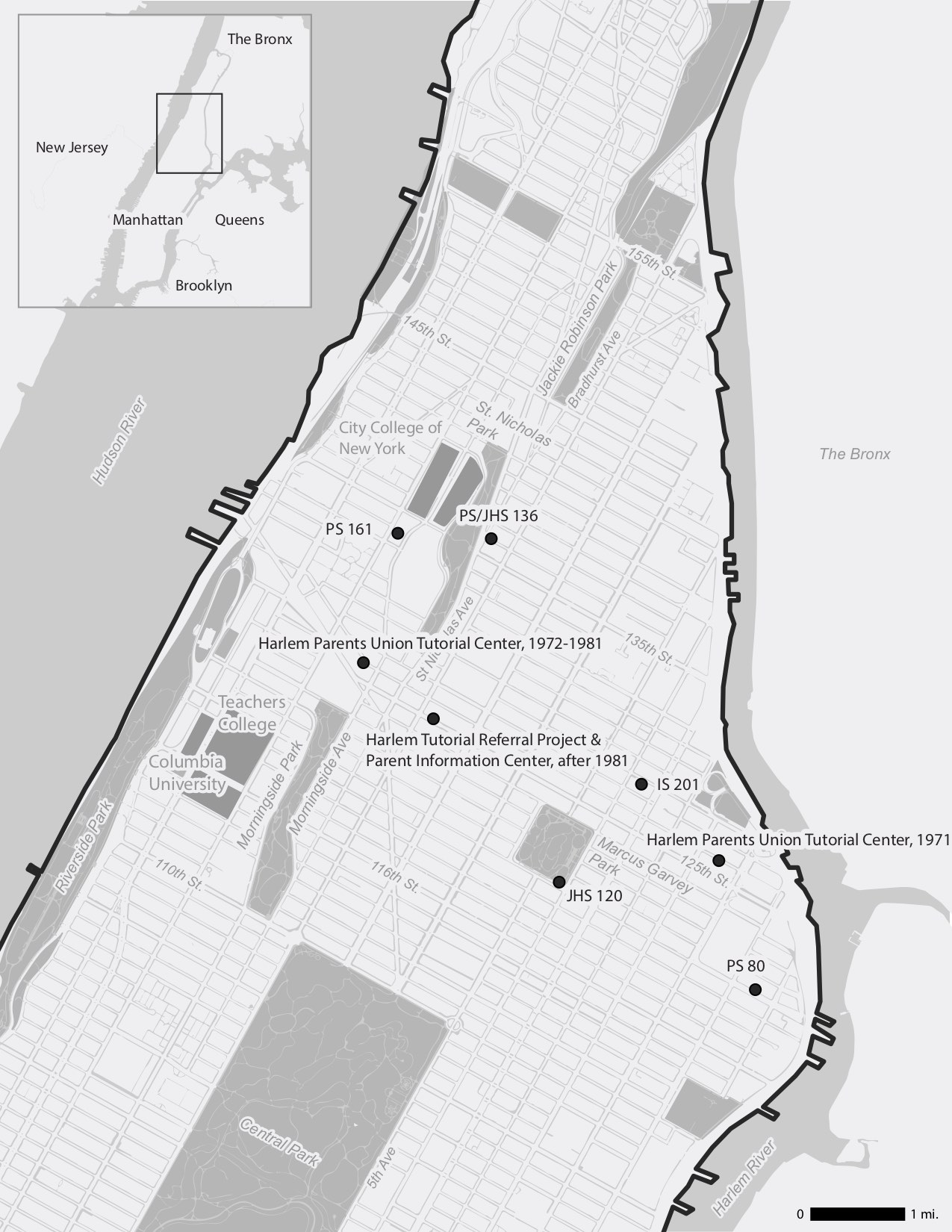

Map design by Rachael Dottle and customized for chapter by Rachel Klepper. Map research by Rachel Klepper. Map layers from: Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, Department of Urban Planning, City of New York; Atlas of the city of New York, borough of Manhattan. From actual surveys and official plans / by George W. and Walter S. Bromley New York Public Library Map Warper; Manhattan Land book of the City of New York. Desk and Library ed. [1956]; New York Public Library Map Warper; and State of New Jersey GIS. Point locations from: School Directories, New York City Board of Education, New York Amsterdam News via ProQuest Historical Newspapers, and multiple archival sources cited in relevant chapters. See maps of the locations discussed in the full volume here.

The longtime educational activist Babette Edwards defies easy characterization. In 1966, she fervently supported the push for community control in Harlem. As a Harlem resident and parent to two young boys, Edwards joined Milton Galamison, David Spencer, and other civil rights leaders to demand community control of Harlem schools. She invited Stokely Carmichael, at that time the face of the Black Power movement, to show support for parents at Harlem’s Intermediate School (IS) 201, as they demanded a greater say in how the new community-controlled complex would be governed. Less than ten years later, Edwards shifted away from the idea of community control within state-run schools and instead pushed for vouchers that would provide funds for low-income Harlem students to attend private schools. Edwards’s fellow voucher proponents included conservative white politicians like Rosemary Gunning—infamous for leading white mothers in Queens on an anti-integration march in 1964. Edwards would continue to cultivate dynamic and perhaps counterintuitive alliances in pursuit of a quality education for Black and Latinx students.1

Babette Edwards’s career as a reformer illuminates the goals, roadblocks, and compromises that Harlem parents and activists navigated in pursuit of an excellent education for their children and reveals the connections between seemingly distinct education reform efforts. Edwards doggedly pursued academically rigorous schooling that would be accountable to parents. Although she thought that well-informed parents and school leadership free from “interest groups” such as the New York City Board of Education and the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) would support effective education, Edwards’s preferred mechanisms for realizing these conditions changed widely over her career. Disappointed with a community-control experiment that she felt failed to live up to its name, Edwards backed tuition vouchers and later supported charter schools as ways around the city’s entrenched educational bureaucracy. She saw vouchers and charter schools as community control over schooling, not merely neoclassical economics. This chapter argues that Edwards juggled a sense of responsibility to Harlem youth with a deep pessimism about the city’s willingness and ability to serve those children through public schools. Her reform efforts demonstrated she had faith that informed parents could ensure high-quality education for their children, and thereby usher in system-wide educational improvements in Harlem.2

IS 201 and Community Control

Babette Edwards was born and educated in New York City. She attended George Washington High School in Washington Heights. Edwards rarely spoke about her own education, though she wrote that her experiences as a student gave her direct knowledge of the “cumbersomeness” of the city’s educational bureaucracy. She instead claimed that her neighbors prompted her first school-based activism. Neighbors who saw Edwards interact with the management at the housing complex where she resided asked her for help advocating for their children at Harlem’s nearby Public School (PS) 80. Edwards remembered PS 80 as a bleak and dismissive space. She recalled incidents in which a teacher struck a student’s face so hard that the student came home with a welt, and another incident in which the principal brushed off a mother’s concerns by claiming that no third-grader should be expected to know how to read. By the time Edwards’s two sons were old enough to attend school, “I was pretty much disgusted with what I saw . . . [and] I wasn’t going to sit back and let my own children be treated in that manner.”3

Edwards became involved with broader educational activism during the 1964 school boycotts against segregation in New York City schools. She performed various tasks for the Harlem Parents Committee, which organized the boycotts. Edwards became active in parent groups at PS 161, where her sons attended school through the mid-1960s. She praised the fact that parents enjoyed some oversight of the curriculum and school governance, though she later lamented the school’s low reading scores. Edwards’s involvement snowballed. By the end of 1966, she had marched overnight in single-digit temperatures to demand integrated schools, had agitated for the proposed IS 201 to become a community-controlled venture, and had been arrested for sitting in at the Board of Education headquarters alongside the more widely known educational activists Milton Galamison and Ellen Lurie.4

Edwards became a major player in the fight for community control at IS 201 (which is detailed in chapters 8 and 9 of this volume). She joined the IS 201 negotiating team, and later served as a community representative to its governing board. She pushed for meaningful community decision making over school personnel and finances. Anything less than true decision-making power was merely the “illusion of control.” She called out “middle-class do-gooders who have allowed the Board of Education to keep them in an advisory status and who themselves have kept communities ignorant” by accepting leadership in name only. Edwards routinely contacted parent groups, Board of Education officials, and local media outlets to demand what she viewed as legitimate community control.5

Edwards’s commitment to this robustly democratic version of community control led to her disappointment with the brief community-control period at IS 201, and her frustration only grew as New York City replaced community control with decentralization. Even while IS 201 remained technically independent of a decentralized school district, Edwards grew tired of internal attempts to quash parent participation at the complex. After four years on the governing board of IS 201, Edwards resigned in 1971.6

Her resignation letter, coauthored with fellow parent-activist Hannah Brockington, reaffirmed her vision of community control and scolded those who did not share it. The letter began, “For the last fifteen years we have fought those people who have deliberately crippled our children. Now in 1971 we are still fighting the same fight, only conditions are worse, because the cripplers in the past (largely white) have now been joined by destructive opportunist education pimps (largely black), who prey on the Harlem community, sucking [its] life’s blood, the community’s future, which is embodied in their children.” Edwards and Brockington accused IS 201’s principals and teachers of betraying Harlem students by siding with the Board of Education and majority-white unions over Black students. These educators thought of Harlem schools “not as a place where children learn” but as a stepping-stone in their own careers, Edwards and Brockington alleged.7

The pair blamed a lack of achievement at the school complex on these Black professionals who, in their eyes, treated Black parents and children with the same contempt as did their white counterparts. Edwards and Brockington proclaimed that Black educators showed a “perverted allegiance” to the city’s central Board of Education. Brockington and Edwards’s resignation letter made clear that not every educator fit this description, though they alleged that prioritizing professional allegiances over duties to Black children and their families was common practice. Edwards and Brockington expressed frustration with parents who sided with school leaders, saving their praise for those parents who “realiz[ed] that when all is said and done, they are the only true protectors of their children.”8

Edwards’s skepticism of “professionalism” traced back to the earliest days of IS 201. She associated the term with the Board of Education’s early efforts against community control. Edwards wrote that during the initial fight for Black leadership at IS 201 in the mid-1960s, “professionalism was an enemy ideology, . . . a euphemism used to describe the interests of people who ran an abominable school system” that excluded Black leaders and undervalued Black students. She continued to distrust “professionalism” as a justification for shifting control of the school to employees over parents—even at IS 201, where many of the school’s leaders and teachers were also Black.9

Edwards’s antiprofessional stance raised some controversy. As her resignation letter alluded, she had butted heads with other parents at IS 201, not to mention with teachers and principals. Many disagreed with her assertion that Black professionals bore responsibility for IS 201’s shortcomings. Her fellow IS 201 governing board member Charles Wilson pointed to state interference, as well as overt opposition from unions, politicians, and whites who benefited from the existing school system, as the main obstacles to effective community control. The IS 201 principal Ronald Evans criticized the “defeatism” of those who blamed the demise of the community-control experiment on Black educators. But Edwards believed that meaningful reform would come only when parents could hold educators accountable. In the 1970s, she embraced vouchers as a tool that might enable Black and Latinx parents to do just that.10

Voucher Advocacy

Edwards lay the groundwork for expanding parent involvement in schools through the Harlem Parents Union. Originally a splinter group from within the Harlem Parents Committee, the Harlem Parents Union separated in 1970 and soon incorporated as its own nonprofit group with Edwards at the helm. The organization tutored Harlem schoolchildren, advocated for students at the individual and community level, and “challenge[d] the widespread notion that home conditions are responsible for poor academic achievement in isolated minority communities.” It also sponsored workshops and conferences for parents, including a 1973 conference on Consumers and Public Education that would prefigure Edwards’s own framing of parents as “consumers” of education. Edwards wrote in a 1977 anthology on school choice that parents should be the drivers of their children’s education, but principals and teachers often stifled them. She lamented that school employees stamped out any sustained effort by parents to interrogate the curriculum or the teachers. The surest way up was out, Edwards suggested.11

Edwards first requested vouchers for Harlem students in February 1975. Petitioning the state commissioner of education on behalf of students in Central Harlem, Edwards’s letter—and a half dozen that would follow—emphasized the burdens that substandard schools wrought on poor families of color. Though nearly 90 percent of students in Central Harlem schools had scored below grade level on the latest citywide literacy tests, their families had no recourse. Edwards wrote that while families in “rich, white communities” enjoyed higher-quality public schools and the ability to send their children to private schools of their choosing, families in “poor Black and Puerto Rican areas” had no choice but to subject their children to ineffective schooling. Without an education that justified their required presence in schools, “the children here are literally incarcerated.” Doubtful of the city school system’s ability and will to change, Edwards demanded that the state provide poor families an escape hatch: school vouchers. She wagered that credits toward private-school tuition, tutors, or new community-run schools would give parents a measure of real decision-making power over their children’s education. A sluggish response from the commissioner’s office prompted Edwards to ask, “How much more do we have to suffer before you respond to our predicament and make up your mind to do your duty as a public servant?”12

In September 1975, seven families answered Edwards’s question by withdrawing their children from the local public schools. All seven families belonged to the Harlem Parents Union, though some hailed from the Bronx and Brooklyn. The parents charged the local schools with failing to meet the burden of an adequate education. By withdrawing their children, they risked a summons to family court for violating compulsory attendance law. The New York Amsterdam News and the New York Times reported on the boycotting families, identifying Babette Edwards as their spokesperson. Edwards and the Harlem Parents Union negotiated with city Board of Education representatives and State Commission on Education leaders on the parents’ behalf. The Harlem Parents Union provided tutorial instruction to eleven boycotting students for a full school year. From nine in the morning until three in the afternoon, volunteers provided personalized tutoring at the group’s Harlem Parents School-Community Neighborhood Center.13

Edwards had been inspired in part by the 1958 boycott organized by the “Harlem Nine” to protest segregation and unequal conditions in three Harlem junior high schools. She had worked with some of the boycotting mothers at IS 201, and she even sent updates about the new boycott to Judge Justine Wise Polier, who had been a sympathetic ear when the Harlem Nine boycotters came before the courts for attendance law violations.14

Yet Edwards had not initially pursued a remedy through the courts. She sought state-sponsored vouchers and negotiated with state and local officials who might acquiesce. These conversations often came to dead-ends, with state officials directing her to the local District 5 school board and the city’s Board of Education. Only after the New York Amsterdam News broke the boycott story did a low-level state official respond. He wrote that Edwards’s complaints about student illiteracy and a hostile school environment did not demonstrate “clear-cut evidence of a violation of the law,” and thus the State Education Department would not intervene. Meanwhile, the local superintendent offered the boycotting students intradistrict transfers to four Central Harlem schools. Edwards rejected the offer, noting that two of the schools’ literacy rates were worse than those at a school a student was actively boycotting, and none cracked the top 50 percent in the city’s own rankings. Shuffling students from one failing school to another was not an option. Only vouchers would enable parents to make consequential choices and allow students access to meaningful education, whether through private schooling (including the possibility of a school run by the Harlem Parents Union), supplemental tutoring, or the ability to enroll in a higher-achieving public school district.15

Several historians trace the first serious interest in vouchers to the economist Milton Friedman, who advocated for capitalist principles of competition to improve U.S. schooling. In practice, however, vouchers were first tested in the South immediately after Brown v. Board of Education. Louisiana employed vouchers to evade desegregation before federal courts struck down these discriminatory voucher plans. Edwards focused on vouchers not as past instruments of racial discrimination, but as liberatory tools for marginalized students. She followed the work of Christopher Jencks, who called for voucher programs for low-income students in New York and elsewhere in 1966. Edwards’s records contain numerous articles from early voucher advocates such as Milton Friedman, Francis Overlan, and Benjamin Foster, Jr. She corresponded with each, and even brought Foster and Friedman to Harlem to speak about the benefits of a voucher system (in 1973 and 1977, respectively).16

In addition to spreading the voucher idea to Harlem parents, these academics introduced Edwards to potential allies in a national fight for vouchers. Francis Overlan of the Education Voucher Project at Harvard University introduced Edwards to the New York State Federation of Catholic Parents, a group that supported vouchers for parochial schooling. Overlan believed that Edwards and Catholic voucher supporters could join forces, though Edwards represented “a different constituency with at least in part a different set of concerns.” These Catholic connections helped to propel Edwards to the national stage. One Catholic parent group circulated Babette Edwards’s 1975 pro-voucher speech in print. Most significantly, Edwards briefly joined the Center for Educational Freedom, which brought her to the respective Democratic and Republican platform hearings in 1976. Their alliance was short-lived. The historian Jim Carl notes that the Center for Educational Freedom shared Edwards’s belief that legislation would be the most promising route to vouchers, but rarely seemed to “make the jump from vouchers in support of parochial schools to vouchers in support of urban students.” Still, the group provided a substantially larger platform for Edwards’s message.17

When Edwards first began campaigning for vouchers in 1975, they were virtually untested outside of the South, where they served to maintain segregation. By the mid-1970s, vouchers had gained little momentum, despite some support from small-government conservatives, groups of African American parents in Boston and Milwaukee, policy advocates such as Jencks and Overlan, and Catholic-school supporters. Several districts investigated, then rejected, potential voucher programs in the early 1970s, perhaps due to vouchers’ associations with segregationism and privatization. Edwards’s advocacy told a different story, casting vouchers as a way for low-income students of color to escape failing education systems, and she put a voice and face to the fledgling pro-voucher movement.18

Edwards began direct appeals to policy makers and legislators. In the fall of 1975 through the summer of 1976, Edwards delivered a pro-voucher plea before politicians and policy makers in New York State as well as before the New York State Board of Regents, the State Legislative Forum, and both major party platform hearings in 1976.19

Edwards’s most widely circulated address on vouchers lambasted the failure of New York City to educate Black and Latinx children. Edwards spoke on behalf of the Harlem Parents Union and the more recently formed voucher-advocacy group Citizens Committee for Effective Education. Beyond these two groups, however, Edwards claimed to represent Black and Latinx parents more broadly. Edwards spoke in the first-person plural throughout her statement, referring to a school system that had “wreaked havoc among us” Black and Latinx families. She addressed policy makers as “you,” a comparatively white, affluent, and influential audience.20

Reminding her audience of the school system’s history as a force of mobility for European immigrants, Edwards emphasized the great economic and social costs of a failing contemporary educational system for Black and Latinx children. Not only did the state waste money on ineffective schools, she argued, it “robbed” children of millions of hours of their time and millions of dollars in lost income. Edwards demanded recognition and empathy for Black and Latinx families. “When you are the victim,” she pled, “when it is your children who are unenlightened, unemployed or unemployable, the criminal, the junkie, disillusioned, defeated before they even begin to live, then you see the problem in a different light.” Middle-class parents could remove their children from failing schools with ease, but those of lesser means found themselves without options. “We are forced to be parties to these crimes, merely because we have no other means of educating our children,” Edwards lamented. Although Edwards believed that education should be a public right, she rejected the notion that the New York City public school system was fulfilling its public obligations. The city neglected Black and Latinx children in particular, she alleged. With so low a bar, how could any educational alternatives possibly do worse?21

In her speech and the copies that circulated, Edwards embraced capitalism and pitched vouchers as a natural extension of fundamentally U.S. ideals. Edwards described vouchers as “American as apple pie.” She pointed to the GI Bill, Medicare, food stamps, and existing textbook reimbursements as analogous “voucher systems,” whereby state funding followed individual consumers into private markets. Edwards borrowed here from the charter proponent Francis Overlan of the Education Voucher Program, who had previously drawn parallels to the GI Bill. Vouchers were not a radical departure from a tradition of public schooling, but rather the realization of a tendency toward empowering individuals in pursuit of public goods.22

Edwards ended her statement by highlighting the consequences faced by low-income parents who refused to subject their students to a failing public system. They would risk prosecution under the compulsory education law. Though Edwards did not mention the Harlem Parents Union’s boycott directly, she emphasized the consequences that she and other parents were willing to endure to pursue better options for their children. Educational options mattered, imminently and intimately. Vouchers were a “simple piece of paper” that could instantly create new options for thousands of students.23

Pushing vouchers into existence legislatively, Edwards and the Harlem Parents Union drafted legislation for the state’s first voucher program. State Senator Joseph Galiber, a Democrat from the Bronx, sponsored the bill. Senate Bill 5314 would allow four districts—including Harlem’s District 5—to create a demonstration voucher program and permitted parents in these districts to choose a public or private school in which to enroll their children. Vouchers equivalent to or more than the district’s average per pupil cost would follow each student, with additional funds allocated for “disadvantaged children.” But the monetary value of base and compensatory vouchers was to be determined later, as was the definition of a “disadvantaged child.” Though the bill failed, its presence suggested the Harlem Parents Union’s potential to influence legislative debates about education and to frame debates around how to treat students from disparate backgrounds fairly.24

Also lobbying for voucher schools that year was Rosemary Gunning, a former state assemblywoman and infamous leader of New York City’s 1964 “white boycott” against integration. Gunning drafted an alternate voucher bill just before Galiber’s bill was submitted to the Senate Committee on Finance in March 1977. Gunning’s draft bill offered a standard voucher amount to all pupils in a district, but allowed it to be supplemented with family funds or private donations. Middle-income families could make up the difference between the state voucher and pricier private tuition, granting them access to a larger array of private institutions. Lower-income families who could not afford the gap between a voucher and tuition would again find themselves priced out of private institutions, rendering the voucher a less-effective tool of equalization than the Harlem Parents Union intended. The biggest difference between the Galiber-Harlem Parents Union bill and Gunning’s, however, was that Gunning did not specify which New York City districts would be eligible to participate in the voucher program. Gunning hailed from Ridgewood, Queens, and advocated school choice for white families. The Harlem Parents Union made sure that, if their version passed, Harlem parents would have access to the program. Edwards and Gunning’s alignment on vouchers as a means of circumventing the existing public school system obscured their disparate motivations for doing so, and it prefigured the similarly strange alliances that would emerge in national school choice fights during the last decades of the twentieth century.25

Nothing came of either proposed voucher bill. (A state-run, publicly funded voucher program would not come to fruition until Milwaukee’s School Choice Plan in 1990. Milwaukee’s voucher program would open with extensive backing from Howard Fuller, another community-control activist turned voucher activist, and a coalition of Black school reformers and conservative white politicians.) New York City would not see a large-scale voucher demonstration until the 1990s, and even that was privately funded. With the legislative defeat in New York, waning federal support for vouchers, and unfavorable reactions from voters in New England, the Harlem Parents Union gradually backed away from lobbying for vouchers. They instead worked to facilitate interdistrict transfers and private school scholarships that would allow students to leave Harlem.26

Certainly, not all Harlem educational activists shared Edwards’s enthusiasm for vouchers. Luther Seabrook, the superintendent of Harlem’s District 5, thought Edwards’s decision to embrace vouchers meant abandoning public schools. Edwards responded that vouchers would provide accountability. Black and Puerto Rican representation on community school boards under decentralization had not fixed the underlying school system, she said, and it was “foolishness” to hope that the New York City Board of Education would change of its own accord. Having to compete for families and their dollars might incentivize the public schools to improve, she thought. Seabrook suggested that withdrawing from the public schools might leave those schools and the children attending them in an even worse state. Edwards conceded that was true, but countered that she felt compelled both to retreat from public schools and to fight for them. Edwards described the fight for reform of the public schools alone as a “losing battle.” She described city schools as “failure factories” and questioned how anyone could, in good conscience, “hold a child in a Harlem school.”27

Choice and Charter Schools

School voucher proposals gained little traction in New York City or State, but Harlem became a focal point in efforts for school choice in the form of charter schools. The latter phase of Edwards’s activism for increased parent choice as a way to improve schooling brought her to charter schools during years in which New York’s charter landscape both led and helped shape the national conversation.

Babette Edwards continued her work with the Harlem Parents Union and its Harlem Tutorial Project and served hundreds of students annually. In the early 1990s, the Tutorial Project created a Parent Information and Training Center, formalizing the Harlem Parents Union’s commitment to helping parents navigate their children’s educational options and participate in local school governance. Edwards brokered partnerships with local universities to procure volunteer tutors and to bring computers and the internet to Harlem schools and education centers. She continued to advocate for students directly, navigating Board of Education bureaucracy and local media to shame the Board of Education into providing textbooks for students in a Harlem school that had no textbooks throughout the 1991–92 school year.28

Edwards’s advocacy extended to school choice within the public school system as well. After District 4 experimented with school choice in East Harlem, Chancellor Joseph Fernandez proposed increased school choice across zones and districts throughout the city. It was a modest proposal, reliant on vacant rather than reserved seats, but it was a symbolically important move toward choice, and Edwards expressed support. She insinuated that the chancellor’s plan was too conservative, insofar as it did not extend choice to private institutions, but nevertheless she endorsed it as a major step forward.29

Despite her support for Fernandez’s school choice proposal, Edwards had doubts about the city’s small and alternative school efforts of the 1980s and 1990s. The small schools created in District 4’s school choice effort of the 1970s and 1980s spawned many other small schools across the city, aided by infusions of philanthropic funds in the mid-1990s and again in the 2000s. Edwards remained skeptical, though, claiming that the Board of Education “tend[ed] to sabotage its own alternative programs.” She maintained her consistent criticism of the United Federation of Teachers as an impediment to reform as well, arguing that union members prioritized salaries over students. She felt the long shadow cast over Black and Latinx communities’ relationship with the UFT by the bitter battle over IS 201 and the community control districts in 1968.30

Scholars have noted that voucher programs, choice-based alternative schools, and charter schools share key ideological underpinnings, particularly the belief that increasing educational choice is good either on its own merits or because the pressures of competition will spur all schools to improve. Many historians tie the origins of charter schools to magnet schools, where families could elect to enroll in schools still governed by local school districts. These authors hold that magnet schools initially aimed to spur desegregation by attracting students to specialized programs and that their popularity increased exponentially when federal funds for magnet schools became available in 1984. In New York City, District 4’s small alternative schools were one variation on this theme. For some, charter schools extended the ideas of voluntary enrollment, mission-based schooling, and autonomy in school governance beyond what was possible in alternative schools operating within the conventional school district.31

Although charters soon became aligned with antiunion activism, early versions of the charter school idea took shape within union circles. The Minnesota teachers union leader Ray Budde is often credited with coining the term, and the UFT president Al Shanker with spreading the idea. Under Budde’s model, charter schools meant greater authority to teachers and administrators so that they could innovate, free from heavy regulation and district oversight. Shanker publicized the movement beginning in 1988. (Ironically, both major national teachers unions would later oppose charter schools, particularly over exemptions from collective bargaining agreements and doubts over charters’ effects on educational attainment.) Edwards’s voluminous clippings contain little about early charter school discussions, when unions were key advocates.32

Charter schools slowly gained momentum in New York State. After two failed attempts in 1997, the state legislature passed a charter school bill in December 1998. Governor George Pataki ushered the bill into law by “effectively [holding] the state legislature hostage,” threatening to veto a hefty raise for legislators if they did not move the needle on charter school legislation.33

The resulting Charter School Act of 1998 promised to realize several of the goals that Babette Edwards had articulated for decades. According to the law, charter schools would aim to increase student learning by encouraging innovation, expanding parent and student choice, and shifting to outcomes-based accountability for schools. Charter schools would receive state funds but would “operate independently of existing schools and school districts.” In addition to autonomy from local school districts, charter schools with 250 students or fewer in their first year were to be exempted from the collective bargaining agreements between districts and teachers unions. This arrangement gave charter school boards of trustees much greater authority over personnel decisions. Charter schools thus combined the public funding and relative autonomy that Edwards had named as crucial for meaningful reform during the days of IS 201 and voucher campaigns.34

Although Edwards had been an early leader in voucher advocacy in New York, she was a relative latecomer to the charter school effort in the state. She soon focused on helping parents become informed consumers in an increasingly choice-based educational system. The Harlem Parents Union’s Tutorial Center invited experts from around the state to speak with Harlem parents about the promises and pitfalls of charter schools. The speaker lineups tipped heavily in favor of charter schools, as did Edwards. Just weeks after the charter bill had become law, Edwards and the Parent Information Center pitched an expanded Educational Alternatives Information Center that would be a hub for parents, and jointly run with Teachers College. The center would combat the “misleading propaganda from special interest groups, e.g. the United Federation of Teachers, the New York City Board of Education, etc.” Edwards envisioned voucher and charter options as a one-two punch against ineffective education. They removed New York City schoolchildren from the auspices of the UFT and the Board of Education.35

In 2000, Edwards moved to seize on the new charter school movement more directly—by starting a charter school of her own. Edwards had begun drafting plans for a school in Central Harlem in the mid-1990s, hoping that federal block grants and state education dollars would fund a school within an autonomous Central Harlem school district. When that funding did not materialize, framing the school as a charter allowed plans to move forward. Edwards penned the first letters about starting a charter school in 2000, calling on local leaders and politicians to support her effort. It would be called the Harlem Parents Charter School, she announced, and would act as “a safe, nurturing oasis” for students in Central Harlem.36

Edwards’s initial description of her planned school focused on the role of parents as key partners in the future school’s development and on “academic excellence” as the school’s central pillar. An organizational chart for the school’s proposed leadership structure depicted the Board of Trustees as equal partners with a Community Advisory Board, which would include the Harlem Parents Union as a “founding partner.” Although Edwards claimed that the school would aim “to help all youngsters in Harlem achieve their full potential,” she conceded that (like many other charters and alternative schools opening in New York City at that time) the school would need to start small.37

Logistical details about the proposed school shifted over the next two years, but the focus on parents and “academic excellence” remained rock steady. In 2002, Edwards convened a new group, the Harlem Education Roundtable, to develop her idea into a full charter school proposal. With the Harlem Education Roundtable at the helm, the Harlem Parents Union would play a diminished role in the school. The school’s name changed, too, from the “Harlem Parents Charter School” to the tongue-tying “Harlem Education Roundtable Academy for Excellence in Education” to the almost acronymous “HEART Charter School.”38

By the fall of 2002, things were looking up for the school. The recently elected mayor Michael Bloomberg had won unprecedented control over the city’s schools, replacing the more than century-old Board of Education with a new Department of Education led by a chancellor selected by the mayor. Bloomberg and his first chancellor, the attorney Joel Klein, put the city’s resources behind charter school and small public school development. The chancellor awarded a $50,000 grant to the Harlem Parents Union to develop a school plan. The proposed school attracted support from many activists who had been key collaborators on Edwards’s earlier efforts. Lola Langley, who had withdrawn her son from Harlem’s public schools alongside Edwards twenty-five years earlier, acted as treasurer for the Harlem Education Roundtable and was named as a board member for the charter school. Hannah Brockington, who had served on (and quit) IS 201’s governing board with Edwards, wrote in support of the school, as did several community partners. Edwards’s long history gave her a wide and deep base of community support on which to draw in imagining a homegrown charter school.39

Edwards’s planning built up strong momentum, and she selected an experienced Harlem District 5 educator as “headmistress/CEO.” Momentum quickly reversed, however, as struggles over consulting fees complicated the already challenging work of preparing an extensive state application, which asked more than sixty questions about the school’s goals, leaders, and logistics. According to planning documents submitted in 2003, the HEART Charter School aspired to solve the educational crisis by setting high academic standards and giving Harlem families “a real choice” in their schooling, a small-scale realization of the educational goals Edwards had been fighting for over the past thirty-five years. The school aimed to span kindergarten through twelfth grade, starting with kindergarten through second grade and expanding upward by one grade annually. The proposed launch scaled back slightly from Edwards’s original vision to an inaugural class of 250 pupils—the maximum number of students that would allow the school to operate without a unionized teaching faculty.40

The school’s academic plan included boilerplate goals—meeting existing state standards and providing students “a strong foundation” in reading, mathematics, science, social studies, and the arts. The school’s charter application used the same language of accountability that Edwards had been using for thirty years, promising to show quantitative results (now measured by state tests).41

Compared to her earlier work on community control at IS 201, Edwards’s charter school said much less about parents as a part of school governance. A draft application referred to parents as key to the school’s development, going so far as to rate them as the most important partner in the school’s design, but the application gave the role of teachers more specific attention. The school’s extended mission statement called for teachers to be respectful, responsive, and collaborative regarding students’ needs and learning. Parents were only mentioned insofar as they were to be “actively involved in the process”—but how or with what authority was not specified. The school specified measures through which it would demonstrate accountability to parents—frequency of parent-teacher conferences, “the degree to which parents demonstrate a knowledge” of their children’s academic interests, even “the level and frequency of parent complaints regarding all aspects of School operations.” And parents would be involved in seminars and workshops about the school’s goals. But Edwards’s earlier emphasis on parents as school decision makers had faded, and was replaced by an emphasis on the choice parents made to enroll their child in the school and on the academic outcomes the school would achieve.42

The HEART Charter team sought resources from the Walton Family Foundation for a $10,000 startup grant. Walton, with the wealth of the Wal-Mart (now Walmart) empire to draw on, had awarded over $30 million to charter schools in less than a decade. Walton did not support the HEART Charter, and plans for the school came to a standstill. The State University of New York (SUNY), one of the state’s charter-granting bodies, received Edwards’s application in fall 2004. While SUNY recorded the application as “withdrawn,” Edwards recalled that it was rejected by Chancellor Klein. Because the Harlem Education Roundtable championed parents, Edwards explained, “Klein could not stand us.” She understood the rejection as “purely political” and noted that it “thoroughly de-energized” the roundtable’s efforts.43

By 2007, Harlem housed fifteen charter schools, most of which now belong to multischool charter management organizations. Early media coverage of the city’s charter schools emphasized how students at charters outperformed their peers at traditional public schools, even as some community members wondered whether this success came at the direct expense of traditional public schools. Increased academic performance as measured by the newly reorganized Board of Education—a formula that included student scores on state tests and attendance rates—indicated charters’ success.44

The Harlem Children’s Zone and its Promise Academy charter drew intense media attention. As the New York Times reported, the Harlem Children Zone founder Geoffrey Canada appealed to both liberals and conservatives by “pouring money into schools” and “directly taking on the problems of inadequate parenting.” The Promise Academy’s “no excuses” style, with its emphasis on intensity and highly disciplined behavior, was shared by other Harlem charter operators as well, and remains at the core of debates over the means and ends of schooling.45

Neither the “no excuses” model nor intervention into parenting practices had been part of Edwards’s vision for school choice, but in many ways her work had set the stage for the predominance of parent choice in Harlem. Edwards’s thinking about the role of parents in education had evolved, from a commitment to parents as participants in democratic governance of schools, to a conception of parents as informed consumers in a choice-based educational marketplace. Yet by the early 2000s, decisions about the shape of charter schooling made far from Harlem now left no place for Edwards’s own community-specific vision of parent choice and quality education.

Edwards’s long career suggests a painfully perpetual quest for effective education for low-income and Black and Latinx children, and for granting their parents a meaningful say in their schooling. Her work provides a window into the possibilities and limitations of in-school reform in Harlem during the latter decades of the twentieth century. Thousands of parents and students directly benefited from the Harlem Parents Union’s workshops for parents and tutorial programs for students from the 1970s through 2003. But its efforts to bring widespread school choice and school governance to parents in support of robust community control were less successful. School choice options remained modest and dictated in large part by figures outside of Harlem. In her doctoral dissertation, completed in the midst of her pro-voucher advocacy in 1977, Edwards wrote that any successful education reform would require three crucial characteristics: it would have to “put real power into the hands of parents,” grant parents a measure of choice for their children’s schooling, and provide incentives for the public education system to improve. Edwards’s willingness to deploy diverse strategies and to build issue-based partnerships with unlikely allies demonstrates the dexterity with which she navigated existing political systems in pursuit of these goals. Questions of how best to make schools responsive to parents and how to bring about meaningful school improvements guided Babette Edwards’s half century of educational activism, and they remain vital but unresolved questions for education reformers today.46

To learn more about the topics and themes explored in this chapter, take a look at the reading and teaching resources, timeline, and maps.

| Previous: Chapter 11 | Next: Chapter 13 |

-

“Parents Stage Tear-In at Board of Education,” New York Amsterdam News, March 19, 1966, 25; Sonia Song-Ha Lee, Building a Latino Civil Rights Movement: Puerto Ricans, African Americans, and the Pursuit of Racial Justice in New York City (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 176; and Matthew Delmont, Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016), 46. ↩︎

-

For a sample of the myriad routes parents and educational reformers pursued to provide Black children a quality education in the later decades of the twentieth century, see Elizabeth Todd-Breland, A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago since the 1960s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Michelle A. Purdy, Transforming the Elite: Black Students and the Desegregation of Private Schools (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Ansley T. Erickson, Making the Unequal Metropolis: School Desegregation and Its Limits (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017); Russell Rickford, We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); and Jack Dougherty, More Than One Struggle: The Evolution of Black School Reform in Milwaukee (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004). ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards, “Responses to Application Questions 1, 2, & 3,” n.d., box 18, folder 18, Babette Edwards Education Reform in Harlem Collection, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library; (hereafter BEERHC); and Babette Edwards, interview with Luther Seabrook, March 1977, box 17, folder 10, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Babette Edwards, interview with Luther Seabrook, March 1977, box 17, folder 10, BEERHC; Harlem Parents School-Community Neighborhood Center, Grant Application [likely to Whitney Foundation], n.d. [likely 1977], box 20, folder 15, BEERHC; “Here Is List of Vigil Keepers: Walking Around the Clock in Racial Harmony!” New York Amsterdam News, January 23, 1965, 1; Sara Slack, “Warn of More 201 Trouble,” New York Amsterdam News, October 15, 1966, 1; and “Galamison and 11 Seized in Sit-In at School Board,” New York Times, December 22, 1966, 1. ↩︎

-

Negotiating Team of I.S. 201, press release, October 3, 1966, box 8, folder 8, BEERHC; E. Babette Edwards, “Additional Letters: Board of Ed,” New York Amsterdam News, June 10, 1967, 17; Sara Slack, “Sutton Says Give IS Board a Chance,” New York Amsterdam News, February 24, 1968, 1; E. Babette Edwards, “District Lines, Election Procedures, and Governing Boards,” March 13, 1969, box 39, folder 5 (Writings, Interviews and Speaking Engagements), BEERHC; and Babette Edwards and Preston Wilcox, “What Happened to Community Control?” New York Amsterdam News, December 11, 1971, A7. ↩︎

-

Harlem Parents Union, press release, April 8, 1971, box 5, folder 8, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Babette Edwards and Hannah Brockington to Dave [Spencer], February 5, 1971, box 5, folder 3, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Babette Edwards and Hannah Brockington to Dave [Spencer], February 5, 1971, box 5, folder 3, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Edythe Babette Edwards, “A Review and Analysis of Three Educational Strategies for Positive Change in the Public School System of the City of New York,” 56, 1977, box 39, folder 2, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Emile Milne, “IS 201 & Decentralization: Trouble—But Still Alive,” New York Post, May 18, 1971; Charles Wilson, “School Problems Show We’re in Deep Trouble,” New York Amsterdam News, December 11, 1971, A7; Ronald Evans, “Lessons Gained in the Struggle,” New York Amsterdam News, December 11, 1971, A7; and Babette Edwards and Preston Wilcox, “What Happened to Community Control?” New York Amsterdam News, December 11, 1971, A7. ↩︎

-

Annie Stein to “To Whom It May Concern,” February 11, 1975, box 39, folder 3, BEERHC; E. Babette Edwards, “Why a Harlem Parents Union?” in Parents, Teachers, and Children: Prospects for Choice in American Education, ed. James S. Coleman et al. (San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies, 1977), 60; “Consumers and Public Education Conference Report,” 1973, box 15, folder 6, BEERHC; Edwards, “Why a Harlem Parents Union?,” 60, 61, 63; and E. Babette Edwards to Steve Williams, April 15, 1996, box 15, folder 1, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards to Ewald B. Nyquist, February 10, 1975, box 22, folder 16, BEERHC; Sterling S. Keyes to E. Babette Edwards, March 25, 1975, box 20, folder 15, BEERHC; and E. Babette Edwards to Ewald B. Nyquist, August 21, 1975, box 24, folder 4, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

WNBC-TV, Transcript of Editorial on Quality Education, November 9, 1976, box 14, folder 2, BEERHC; Harlem Parents School-Community Neighborhood Center, Grant Application [to Whitney Foundation?], [1977?], box 20, folder 15, BEERHC; Harlem Parents Union, Inc., Press Release re: Parents Boycotting Failing Public Schools in New York City, January 19, 1976, box 20, folder 15, BEERHC; Simon Anekwe, “Black Parents Seek State Funds for Private Schools,” New York Amsterdam News, October 8, 1975, C9; “Boycotting Parents Want Funds Used for Private Schools,” New York Times, January 22, 1976, 74; E. Babette Edwards to Irving Anker, September 13, 1976, box 14, folder 9, BEERHC; Thomas A. Johnson, “7 Parents Defying Schools by Setting Up Their Own,” New York Times, November 2, 1976; and Joseph W. Horry, Summary Report on alternative schooling, June 16, 1977, box 17, folder 5, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Adina Back, “Exposing the ‘Whole Segregation Myth’: The Harlem Nine and New York City’s School Desegregation Battles,” in Freedom North: Black Freedom Struggles Outside the South, 1940–1980, ed. Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 65–93; and Justine Wise Polier to Babette Edwards, December 2, 1975, box 14, folder 2, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Babette Edwards, interview with Luther Seabrook, March 1977, box 17, folder 10, BEERHC; Anthony E. Terino to E. Babette Edwards, October 10, 1975, box 24, folder 4, BEERHC; Simon Anekwe, “Black Parents Seek State Funds for Private Schools,” New York Amsterdam News, October 8, 1975, C9; E. Babette Edwards to Alfredo Matthew Jr., February 5, 1976, box 20, folder 15, BEERHC; Harlem Parents School-Community Neighborhood Center, Grant Application [to Whitney Foundation?], [1977?], box 20, folder 15, BEERHC; and “Positions of the Citizens Committee for Effective Education on Various Questions,” [1975], box 24, folder 5, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Jim Carl, Freedom of Choice: Vouchers in American Education (Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger, 2011), 16, 24; Lisa Stulberg, Race, Schools, and Hope: African Americans and School Choice After Brown (New York: Teachers College Press, 2008), 81–86; S. Francis Overlan, “Regulated Compensatory Voucher Plan,” April 1973, box 13, folder 19, BEERHC; Benjamin Foster Jr., “The Case for Vouchers,” May–June 1973, box 22, folder 16, BEERHC; Milton Friedman, “The Role of Government in Education,”1962, box 22, folder 16, BEERHC; E. Babette Edwards to Benjamin Foster Jr., October 11, 1973, box 14, folder 1, BEERHC; and “How to Put Learning Back into the Classroom,” lecture flyer, September 15, 1977, box 18, folder 5, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

S. Francis Overlan to E. Babette Edwards, February 26, 1975, box 14, folder 1, BEERHC; E. Babette Edwards, “Speech to the New York State Board of Regents,” September 10, 1975, box 18, folder 5, BEERHC; and Carl, Freedom of Choice, 99. ↩︎

-

Stulberg, Race, Schools, and Hope, 70–82; and Dougherty, More Than One Struggle, 115–16. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards, Resume, 1976, box 39, folder 5 Writings, Interviews and Speaking Engagements, BEERHC; Edward F. Spiers, Request for Appearance at 1976 Republican National Convention Committee on Resolutions (Platform), box 14, folder 2, BEERHC; Edward F. Spiers to E. Babette Edwards, May 6, 1976, box 14, folder 2, BEERHC; and E. Babette Edwards, “Statement to the Democratic Party Platform Committee,” May 20, 1976, box 23, folder 1, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards, “Speech to the New York State Board of Regents,” September 10, 1975, box 18, folder 5, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards, “Speech to the New York State Board of Regents,” September 10, 1975, box 18, folder 5, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards, “Speech to the New York State Board of Regents,” September 10, 1975, box 18, folder 5, BEERHC; and S. Francis Overlan, “Regulated Compensatory Voucher Plan,” April 1973, box 22, folder 16, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards, “Speech to the New York State Board of Regents,” September 10, 1975, box 18, folder 5, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards and Joseph W. Horry Jr., “Interim Report—August and September 1977,” October 19, 1977, box 17, folder 5, BEERHC; E. Babette Edwards and Joseph W. Horry Jr., “Interim Report—July 1977,” August 11, 1977, box 17, folder 5, BEERHC; Mae A. D’Agostino to Babette Edwards, February 2, 1976, box 22, folder 16, BEERHC; and An Act to Create a [Voucher] Demonstration Program, New York S. 5314, 182nd Congress (1977). ↩︎

-

Delmont, Why Busing Failed, 47–48; Rosemary R. Gunning to “Dear Friends,” March 12, 1977, box 23, folder 1, BEERHC; An Act to Create a [Voucher] Demonstration Program; Douglas Martin, “Rosemary R. Gunning, 92, Foe of School Busing,” New York Times, October 7, 1997; and Rickford, We Are an African People, 259–61. ↩︎

-

Dougherty, More Than One Struggle, 180–93; William G. Howell and Paul E. Peterson, Education Gap: Vouchers and Urban Schools (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2005), 34–35; Denis P. Doyle to Babette Edwards, March 29, 1976, box 14, folder 2, BEERHC; Harlem Parents School-Community Neighborhood Center, “A. Student Services,” n.d., box 20, folder 18, BEERHC; E. Babette Edwards and Joseph W. Horry Jr., “Interim Report—August and September 1977,” October 19, 1977, box 17, folder 5, BEERHC; and Joseph W. Horry, Summary Report on alternative schooling, June 16, 1977, box 17, folder 5, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Babette Edwards, interview with Luther Seabrook, March 1977, box 17, folder 10, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards to William Lynch, February 28, 1995, box 22, folder 6, BEERHC; Harlem Parents Union, Inc., “Proposal to Expand Our Existing Parent Training and Information Center,” n.d., box 23, folder 1, BEERHC; “Walton Foundation Grant Application,” May 22, 2003, box 26, folder 2, BEERHC; “Agency Interim Report, School Year 1983–1984,” [1984?], box 22, folder 6, BEERHC; “Proposal to Establish the Harlem Parents Institute,” February 22, 2002, box 22, folder 13, BEERHC; and Sheryl McCarthy, “Other Kind of School Violence,” January 12, 1994, box 39, folder 5 Writings, Interviews and Speaking Engagements, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Babette Edwards, “Future Directions in Obtaining Effective Education,” New York Amsterdam News, January 19, 1980, 11; Joel Handler, Down from Bureaucracy: The Ambiguity of Privatization and Empowerment (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001), 187; and E. Babette Edwards to H. Carl McCall, December 2, 1992, box 4, folder 4, BEERHC. For more on small schools in New York City, see also Deborah Meier, The Power of Their Ideas: Lessons for America from a Small School in Harlem (Boston: Beacon Press, 1992) and Heather Lewis, New York City Public Schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg: Community Control and Its Legacy (New York: Teachers College Press, 2015), 120–37. ↩︎

-

Howard Bloom and Rebecca Unterman, “Sustained Progress: Findings About the Effectiveness and Operation of Small Public High Schools of Choice in New York City,” New York, MDRC, 2013, accessed July 26, 2018; E. Babette Edwards to Isaiah Robinson, April 26, 1972, box 22, folder 15, BEERHC; “Schools Called Anti-Parents,” New York Amsterdam News, April 22, 1972, A1; and Leah Fritz, “A Look at the Schools,” February 1973, box 39, folder 5 (Writings, Interviews and Speaking Engagements), BEERHC. For histories of the animosity caused by the 1968 UFT strikes, see Jerald E. Podair, The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2008); Daniel H. Perlstein, Justice, Justice: School Politics and the Eclipse of Liberalism (New York: Peter Lang, 2004); Lewis, New York City Public Schools; and Jonna Perrillo, Uncivil Rights: Teachers, Unions, and Race in the Battle for School Equity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012). ↩︎

-

Paul E. Peterson and David E. Campbell, “A New Direction in Public Education?” in Charters, Vouchers, and Public Education, ed. Peterson and Campbell (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2001), 5–6, 9; and Handler, Down from Bureaucracy, 186–87. ↩︎

-

Joseph Murphy and Catherine Dunn Shiffman, Understanding and Assessing the Charter School Movement (New York: Teachers College Press, 2002), 22–26, 36–38. For more on the origins of charter schools, see Ray Budde, Education by Charter: Restructuring School Districts (Andover, Mass.: Regional Laboratory for Educational Improvement of the Northeast and Islands, 1988). ↩︎

-

Senate Bills 3252 and 5433, of February and June 1997, were virtually identical to the successful Senate Bill 2850. Lance D. Fusarelli, The Political Dynamics of School Choice: Negotiating Contested Terrain (New York: Pan Macmillan, 2003), 95. For contemporary debates over charter schools, see Iris C. Rothberg and Joshua L. Glazer, eds., Choosing Charters: Better Schools or More Segregation? (New York: Teachers College Press, 2018); and Eve L. Ewing, Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018). ↩︎

-

New York Charter Schools Act of 1998, N.Y. Consolidated Laws: Education, §§ 2850–57; and Babette Edwards, interview with Luther Seabrook, March 1977, box 17, folder 10, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards to Richard Hoke, July 3, 1998, box 15, folder 1, BEERHC; Harlem Parents Union and the Center for Educational Outreach and Innovation, “All the Information You Should Know About Public Charter Schools” flyer, May 1999, box 13, folder 19, BEERHC; and E. Babette Edwards to Verne Oliver, January 12, 1998, box 15, folder 1, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards to Peter Cookson, November 24, 1998, box 18, folder 20, BEERHC; Dr. Roscoe C. Brown Jr., “A Proposal for Establishment of a Harlem Independent School District,” May 18, 1994, box 24, folder 22, BEERHC; Veronica Holly, conversation with the author, May 1, 2018; E. Babette Edwards to David Patterson, July 24, 2000, box 15, folder 1, BEERHC; E. Babette Edwards to Calvin Butts, July 24, 2000, box 15, folder 1, BEERHC; E. Babette Edwards to Herman Badillo, July 24, 2000, box 15, folder 1, BEERHC; and E. Babette Edwards to William Perkins, July 24, 2000, box 15, folder 2, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

E. Babette Edwards to David Patterson, July 24, 2000, box 15, folder 1, BEERHC; and “Envisioned Organizational Structure, Harlem Parents Charter School,” September 2000, box 13, folder 19, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

“Part II Question 1,” n.d. [likely 2003], box 26, folder 3, BEERHC; E. Babette Edwards to David Patterson, July 24, 2000, box 15, folder 1, BEERHC; Michele Cahill to E. Babette Edwards, December 11, 2002, box 25, folder 10, BEERHC; and Peter W. Cookson Jr. to Babette Edwards, January 17, 2003, box 25, folder 9, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

Michele Cahill to E. Babette Edwards, December 11, 2002, box 25, folder 10, BEERHC; “The Harlem Round Table Academy of Excellence,” November 20, 2002, box 25, folder 9, BEERHC; Edythe Babette Edwards, “A Review and Analysis of Three Educational Strategies for Positive Change in the Public School System of the City of New York,” 1977, box 39, folder 2, BEERHC; Harlem Education Roundtable, Form 990-EZ, 2004, accessed February 18, 2019; and Hannah Brockington to E. Babette Edwards, December 4, 2002, box 25, folder 9, BEERHC. For more on the recentralization of the New York City Board of Education, see Lewis, New York City Public Schools, 137–41. ↩︎

-

Sarah Kershaw, “State Regents Battle Schools Chief’s Hiring,” New York Times, December 15, 1995; Regina L. Smith to Marie L. Taylor, February 24, 2003, box 26, folder 2, BEERHC; Mary C. Bounds, A Light Shines in Harlem: New York’s First Charter School and the Movement It Led (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2014), 52–53; and “Walton Foundation Grant Application,” May 22, 2003, box 26, folder 2, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

“Walton Foundation Grant Application,” May 22, 2003, box 26, folder 2, BEERHC; and Perrillo, Uncivil Rights, 157. ↩︎

-

“Walton Foundation Grant Application,” May 22, 2003, box 26, folder 2, BEERHC. ↩︎

-

“Charter Schools: Challenges and Opportunities,” Philanthropy Magazine January/February 2003, accessed February 26, 2018; John F. Kirtley and John Walton, “Annual Meeting Highlights: Salute to Effective Education Philanthropy,” Philanthropy Magazine January/February 2003, accessed February 26, 2018; Ralph Rossi II to Joel Klein, October 18, 2004, New York State Education Department Charter School Unit, Charter School Denied/Withdrawn Applications, box 6 (acc. 20196-07), folder labeled “Heart Charter School Correspondence,” New York State Archives, Albany (hereafter NYSED Charter); James Merriman IV to Joel Klein, November 30, 2004, NYSED Charter; and Babette Edwards, phone conversation with the author, May 28, 2019. Notes in the author’s possession. ↩︎

-

USNY and the State Education Department, Annual Report [ . . .] on the Status of Charter Schools in New York State 2007–08, October 2009, accessed February 16, 2019; and Jennifer Medina, “Charter Schools Outshine Others as They Receive Their First Report Cards,” New York Times, December 20, 2007, B8. ↩︎

-

Paul Tough, “The Harlem Project,” New York Times, June 20, 2004; and A. Chris Torres and Joanne W. Golann, “NEPC Review: Charter Schools and the Achievement Gap,” (Boulder, Colo.: National Education Policy Center, 2018), accessed February 17, 2019. ↩︎

-

Edythe Babette Edwards, “A Review and Analysis of Three Educational Strategies for Positive Change in the Public School System of the City of New York,” 63, 1977, box 39, folder 2, BEERHC. ↩︎